"Aale hu disham le Swadinakada" - indigenous people's contribution to the Swadhinata Juddho

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

It is worth remembering that the freedom the people of Bangladesh enjoy is one that was brought about by not only Bengalis, but also non-Bengalis who did not hesitate to give up their homes, families, livelihoods, and in some cases their lives.

Very little is known about the contribution of the indigenous people to the Bangladesh Liberation War. A large part of this is due to the insurgency in the Chittagong Hill Tracts that has tarnished the image of the tribal people in the eye of the Government of Bangladesh who exert great level of influence in history writing in Bangladesh. However, this should not constitute a cause not to recognise their gallant contribution for the freedom of a country that is also theirs.

During 1971 many indigenous Bengalis such as Shantal of the north, Orao, Dalu, Malpahari, Chakma of Chittagong Hill Tract, Marma, Tripura, Garo of Mymensingh, Hajong, Coach, Manipuri of Sylhet (including workers of tea gardens) took part in the War of Independence, sheltered the freedom fighters, built resistance against the occupation forces and faced the enemy with bows and arrows. Training centres for freedom fighters were also set up at Rangamati and Ramgarh Sadar in Chittagong district. Some 1,300 Garo, Hajong and Coach communities from greater Mymensingh region is believed to have participated in the war. Of them, 115 people fought under Sector 11 (Mymensingh-Tangail) at Haluaghat and few of them embraced martyrdom.

The indigenous people, or 'adivashi' in Bengali, fought hand in hand with their fellow Bengalis and inspired and organised other members of their community to participate in the war. They did not view the fight as something concerning the Bengalis exclusively but one which was aimed at liberating the people of Bangladesh, of which they were a member. It was their fight too. However, this 'freedom' had heavy cost for them too. They lost their land and property and suffered repression. Some had even ignored the threat of their landlord who were local collaborators of the Pakistani occupation forces, only to feel the wrath of family members of these landlords post-independence. Event today, these powerful elements are prone to evicting the adivashis from their ancestral land.

Freedom fighter Uttam Kumar Sarder said he felt "ignored and inferior" before people around him in India, where he had fled at the beginning of the Liberation War in 1971.

Despite such humiliation, like many other indigenous people, he undertook training in guerrilla warfare and returned to the country to fight against the Pakistani occupation forces. He fought several battles on the war front and was once caught and tortured by local collaborators of the Pakistani forces.

I also took part in battles on behalf of Kaderia Bahini and after freeing Tangail from the Pakistani forces on December 11, I stayed at Bindubasini High School camp. Later I surrendered my arms to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman at the school ground and returned to my village. Now at 70, I have to work as a day labourer for Tk 70 to Tk 80 per day for living.

I joined the Liberation War with a hope to eradicate oppression and immoral practices but we the indigenous people are facing oppression and torture.

We did not fight for such a country.

Muktijuddha Chin Sangma of Dharati village in Tangail laments the ill-treatment of adivashis

Denial of equal rights

The defection of influential Chakma leader Raja Tridev Roy to the Pakistani side and the subsequent years of conflict between the Government of Bangladesh and the Shanti Bahini of the Chittagong Hill Tracts intensified the hostility towards the adivashis.

Post-independence various indigenous groups have regularly complained of ill treatment by the Government of Bangladesh and the majority Bengali population. Common complaints include denial of equal social and economic rights, non-recognition of ethnic identity within the Constitution of Bangladesh, non-recognition of contribution during Muktijuddho, illegal land grabbing, and indifference of the authorities to preserve their culture and language, leading towards a steady decline of their ancestral heritage.

The adivashis feel that the majority (Muslim-Bengali) people of Bangladesh has failed to realise and appreciate the diversity in Bangladesh in terms of culture and religion, resulting in discrimination, conflict and deprivation. According to Professor Mesbah Kamal of Dhaka University, General Secretary of Bangladesh Adivasi Odhikar Andolan (Indigenous People's Rights Movement Committee), it's important for Bangladesh to take initiative which "shows respect to plurality and cultural diversity of the country" and ensure equal rights to people from other cultures.

Many indigenous people, including brave freedom fighters, are now working as day labourers and find it difficult to survive on daily basis and meet their basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter.

Organisations such as Bangladesh Adivashi Forum, Bangladesh Adivashi Parishad, Bangladesh Adivashi Adhikar Andolon, Research and Development Collective, Adibashi Sangskritik Unnayan Shangstha (ASUS), Working Journalists for Indigenous Community are driving the efforts for the adivashis to receive the due honour and recognition from the state. They are working to readdress this balance and provide a realistic picture of 1971 to future generations.

They did not want anything from the state and the state also did not give them any reward.

Sanjib Drong, writer and researcher

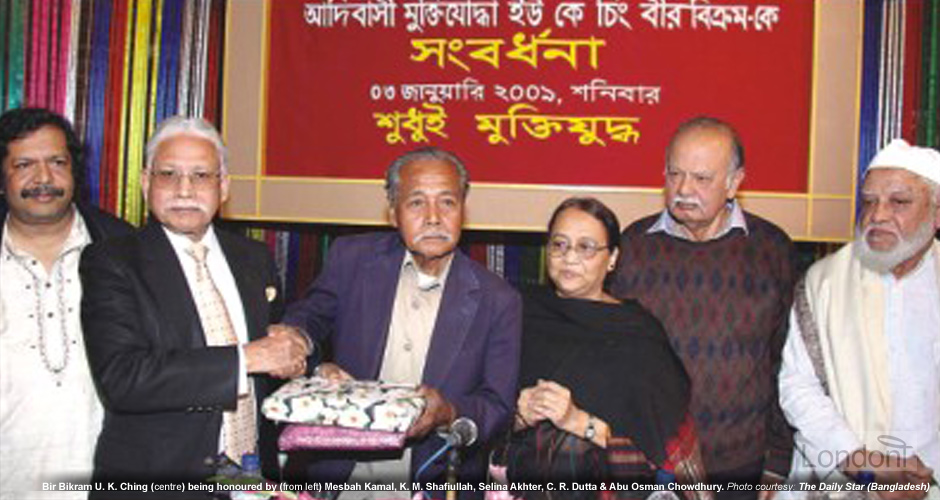

U. K. Ching - the only adivashi to be awarded state recognition

U. K. Ching belongs to the Marma community - the second largest ethic minority group in Bangladesh behind the Chakmas - of Ujanipara in Bandarban, Chittagong Division. During 1971 he was a naib subedar of the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) stationed at the Hatibandha border outpost in Rangpur Division when the war began and joined the war after he had come to know of the brutality perpetrated at the EPR headquarters at Pilkhana, Dhaka.

As a member of the EPR, he fought in many districts as a platoon commander. He fought at the battles at Gangamari and Chowdhury Hat in Chittagong district and describes the Chowdhuryhat battle in particular as a "deadly battle" and one he "survived by luck". Alongside guns, U. K. Ching used indigenous tools and tactics against the Pakistan army. His ingenuity amazed the muktijuddha war commanders. He also fought in the Rangpur district and took part in blowing up the Lalmonirhat power station. U. K. Ching was a courageous soldier who only lost 3 of his men in the nine months of war and took initiative to rescue many Bengali women from the hands of the Pakistani army.

In the course of war U. K. Ching came in contact with Indian General Jagjit Singh Aurora and martyred Bengali war hero Lieutenant Abu Moyen Mohammad Ashfaqus Samad.

U. K. Ching ()

U. K. Ching ()

After independence U. K. Ching was awarded Bir Bikram - Bangladesh's fourth highest gallantry award - by the Government of Bangladesh in recognition of his contribution. Till today, U. K. Ching remains the only member of the ethnic minority communities to have been awarded such recognition.

U.K. Ching's journey from near obscurity to recognition is one that should give the nation pause. There is little information about his contributions in the war and hardly any documentation about this gallant hero in official records.

U.K. Ching's experience in the frontlines is a testament to his valour and his indomitable spirit in the quest for freedom. Now around seventy-five years old, he is still a feisty man with a sparkling sense of humour, which was manifest in the war stories he related.

Now frail and reaching his 80th birthday, U. K. Ching is leading a life of hardship with his 8 family members. He cannot work hard due to his illness and does not receive any support from the government. Even a national hero like U. K. Ching was at the receiving end of mistreatment which has been the longstanding experience of many of his fellow members of the ethnic communities. After shifting from Bandarban town to the outskirts of Langipara, U. K. Ching tried to develop an orchard of teak but local hoodlums occupied it.

If these [ethnic and religious maltreatment] continue, how could you claim there is no disparity?

I can say it from my condition. It is tough to arrange three meals now. I had a house in Bandarban town but had to sell it to cope with financial hardship. I had written to the Prime Minister for an auto-rickshaw but there was no response. I can assess the condition of others through my condition.

U. K. Ching believes the goals of Liberation War, such as the abolition of economic disparities among citizens, remains a remote reality even after four decades of independence. The sustained maltreatment of minority communities - both ethnic and religious - by successive governments leaves him appalled and infuriated. It makes him wonder if the sacrifices he and countless others made to create a new nation had been worth it.

The ideals of the war are yet to be realised and successive governments have completely ignored these ideals. I do not believe they can be met...This is not the Bangladesh that we fought for nine months.

Many people inquire of my condition when March or December comes. For the rest of the year, no one actually bothers.

The political parties come up with a long list of promises such as establishment of basic and civil rights of the people before every general election. However, once they are elected, they forget everything and literally become autocrats. We dreamt of a country where there would be no discrimination on the basis of religion or ethnicity. Unfortunately, in reality, the practice of Punjabis continues.

The state machinery appeared busy in efforts to Islamise the state and has finally done so by making Islam the state religion. Even the Awami League, which gave political leadership to the war of independence, stuck to the agenda.

I do not think I fought for this Bangladesh. I don’t believe the major parties would do away with the communal provision in foreseeable future.

Few other indigenous war heroes:

Shakhipur and Gazipur

- Lakkhan Chandra Barman

- Parimal Chandra Kotch

- Chandra Mohon Barman

- Sona Toch Burman

- Nipen Barman

- Lakhyi Kanto Kotch

- Ajit Chandra Barman

- Jotin Chandra Kotch

- Suresh Chandra Barman

- Rabindra Chandra Barman

- Jotindro Chandro Barman

Rajshahi

- Uttam Kumar Sarder

- Shushil Soren

- Bishwanath Hembrom

- Abatar Mondol

- Hemanta Kumar Murai

- Shukh Chand Murari

- Naresh Chandra Murari

- Shrikanta Murarti

- Biren Murari

- Narayan Murari

- Joy Chand Mondol

- Bisto Chandra Hazra

- Buddinath Orao

- Dasu Murmu

- Thakur Mardi

Others

- Ushit Mong of Cox's Bazar

- Goda Orao of Joypurhat

- Chin Sangma of Netrakona

- Nikhil Hajong of Mymensingh

- Manindra Kishore Tripura of Matiranga in Khagrachhari

- Lawrence Marandi of Joypurhat

- Habel Hemrom of Thakurgaon

I too like many of my compatriot freedom fighters shed blood for our motherland. I can't understand why I still feel ignored and inferior. Why am I not recognised constitutionally?

I underwent torture and returned from the edge of death. These incidents seldom come back in my memory. But I can never forget the day when Pakistani soldiers killed a pregnant woman and then tore her into pieces and severed her baby from her womb.

If we have the same feelings for the country, we have also our right to be recognised in the constitution.

Rebati's anguish

On April 1971 the Pakistani Army attacked the slum in Khadim tea garden in Sylhet. After shooting the men who were hiding among the bushes, they pushed all the women and children inside the huts and set them on fire. Defying fear, 16-year-old Rebati Mahali, a tea-garden labourer of the Mahali indigenous community, broke the shacks and helped the women and children to escape. But she was caught by the army. Dragging her under a tree, the Pakistani army tortured Rebati inhumanely and raped her one by one. Nobody came to her rescue as she screamed for help.

Men were made to stand in two lines and the women and children were all pushed inside the thatched houses. To their horror, the men saw one machine gun was being set up by the soldiers on the high ground in front of them. Before they could understand, the soldiers opened fire at the men standing in the line. Most fell dead and only a few ran and took shelter in the tea-garden. The women and children inside the thatched houses could hear the screaming of their men being killed mercilessly. But they did not understand what lay ahead of them. The soldiers brought petrol from their truck, spread it over the slums and set fire on them. The women and children were somewhat dumbfounded as they had no idea as to how to save themselves.

Rebati watched her mother and few others engulfed by the fire as the women and children began to scream. Brave Rebati made all out effort to break open the bamboo wall of the slum to allow first the children to escape from the fire. She started pushing the children out of the slums. The children ran and took shelter in the tea-garden but many women could not come out. Rebati decided not to run out of the slum but to continue helping the women in distress. From the high ground the army personnel spotted Rebati who was trying to save the others. They caught Rebati and dragged her near the large tree. The soldiers unleashed their anger and hit her and she fell on the ground. The soldiers raped her one by one. Her screams echoed from across the hills and valley. There was no one to help her that day. After committing the heinous crime, the soldiers along with their collaborators left the slum area for more comfortable bungalows of the tea-garden officials.

Even today, over 40 years after she sacrificied her life for the freedom of her motherland, the Mahali people can still hear Rebati's scream echoing in the hills of Khadim tea garden in Sylhet.

I contemplated the answer for sometime and then told them that she comes back because she has not received justice for all these years.

Lt. Col. Zahir on why Rebati continues to haunt the hills of Sylhet

Rebati's tragic story - and many more like hers - only came to light after Liberation War researcher Lt. Col. Quazi Sajjad Ali Zahir 'dug out her story from the lost pages of history that mostly accounted the heroic tales of enlisted freedom fighters and leaders'.

Bangabandhu had intended to honour the sacrifice of Rebati and thousands of women like her with the 'Birangana' title, however because of socio-cultural limitations and our own failure as well as the curse of our patriarchal social system, the word has lost its essence. [I had] Requested many a government to recognise the contribution of women with state honour, but no one has ever listened. We conveniently forget them when we are in power.

Selina Hossain, Literateur

Raising awareness

In 2008, authors Ayub Hossain and Charu Haque co-wrote the research-based book "Muktijuddhe Adivasi" (Indigenous people in the War of Liberation) to highlight the contribution of that community. Air Vice Marshal A. K. Khandaker launched the book and sought recognition and allocation of equal rights for the indigenous people. Referring to several incidents of land grabbing, he said no-one has the right to grab the lands of the indigenous people.

Another active supporter has been Major-General Chitta Ranjan Datta, Sector 4 (Habiganj, Sylhet) commander and Bir Uttam. Major C. R. Datta, as he is popularly known, has been a regular campaigner calling on the government to ensure the rights of the indigenous community and condemned the repression. Being a Hindu, which represents less than 10% of Bangladesh's population, the Major is no stranger to the frustration of the minority.

For the adivashis of Bangladesh they want the state to recognise their freedom fighters and ensure they enjoy equal facilities as the Bengali freedom fighters. They want everyone to be respected irrespective of caste, culture and community.

Muktijoddhas have asked for very little; their demand has always been that the country be built on the values of freedom, dignity and equality, which they fought for. Yet thirty-seven years into independence, the nation has failed its children and the very ideals it was created for.

Successive governments have yet to recognise the role of non-Bengalis in the liberation struggle and have failed to protect, preserve and respect the rights of adivasi communities who are part and package of the diversity of this nation. They are still denied their right to land, language, and culture. They are denied their space in the Bangladeshi constitution, thereby being dismissed as people of no-consequence.

It is a shame for Bengalis who fought so hard for their language, their right to autonomy, their culture and their freedom with the assistance of the adivasi communities, that they have failed the very people with whom they continue to share the water, air and land of this country. Till our adivasi brothers and sisters, neighbours and friends get their rightful position in this country, the struggle for liberation is not over.

A medal means very little if there is little understanding of its true value. Recognition is tainted if it is limited to honouring the contributions of only those of a particular ethnic group, however it is defined - by the colour of one's skin, one's language, one's culture. Freedom loses its meaning if one enjoys it at the expense of another.

U.K. Ching, and men and women like him who gave it their all for independence, did not ask for a medal nor for recognition. They fought along with their Bengali brothers and sisters because it was what they believed they should do during a time of severe crisis. In return, they did not expect the country they fought for to fail them again and again, such that today even their grandchildren continue to be forgotten, their land is grabbed through illegal settlements, and their resistance is silenced by violence and intimidation.

Recognising the dire circumstances in which U.K. Ching and his family now live in, Dr. Zafarullah of Gonoshastho Hospital and Dr. Hasan of Al Biruni Hospital have come forward offering free medical treatment; others have pledged to assist them in any way possible. Yet, such private initiatives cannot replace the role and responsibility of a national government that, in sheer callousness, listed a living hero as being dead.

The heroes of '71 expected more from the country they helped create; at the least, they did not expect to be forgotten. In the case of the adivasis, their contribution in the independence of this country has yet to be recognised, as is their right as equal citizens of this land. They are still waiting for the country to embrace them as its own. They should not have to wait anymore.

Tazreena Sajjad, member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective

It is upto you, my Bengali and adivasi brothers and sisters, to save our country. It is your turn now.

Bir Bikram U.K. Ching speaking at a function organised by Shudhui Muktijuddho