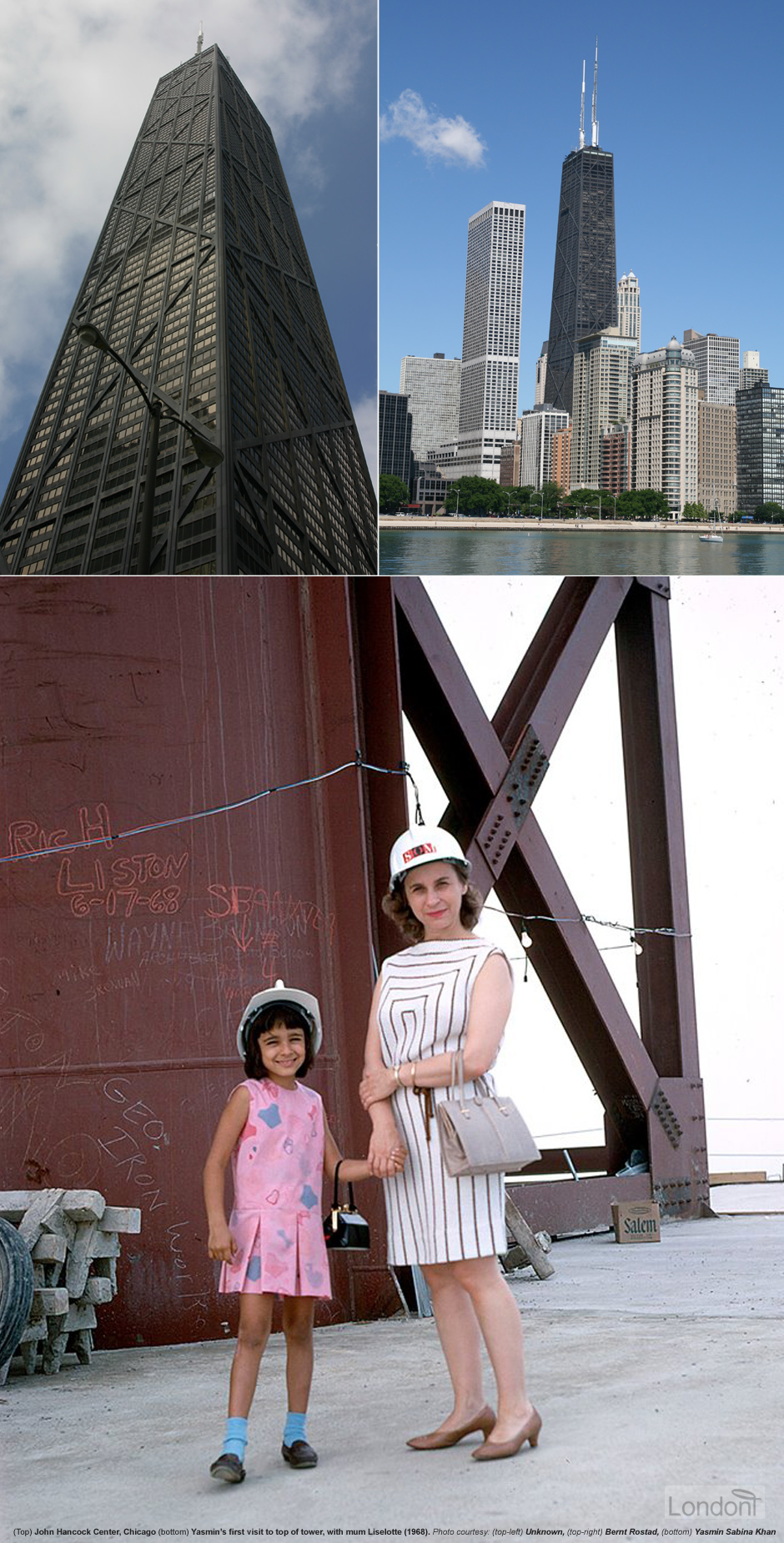

John Hancock Center, Chicago

Last updated: 10 October 2017 From the section Fazlur Rahman (F. R.) Khan

Construction of the John Hancock Center on 875 North Michigan Avenue, Chicago, began on 5 May 1965. It was completed 36 months later, after some 5 million man-hours.

The Hancock was built using Fazlur Khan's diagonal-framed "trussed tube" system for the first time. This approach connected widely spaced exterior columns with diagonals on all four sides of the building, while simultaneously carrying their share of gravity loads. The massive distinctive exterior X-braces supported the building against the wind whipping off Lake Michigan. Early skyscrapers typically were supported by an internal cage of steel columns and beams. Though the cage allowed office buildings to reach once-unthinkable heights, it required a relatively large number of interior columns and chewed up valuable floor space. In contrast, the Hancock's steel tube created vast expanses of column-free space - and it was enormously economical. The tower cost $100 million to build, the cost of a conventionally supported, 45-story office building.

Every great engineer must have courage in crisis. This Khan proved in abundance when he stopped the works on the Hancock Center after a slight shift in one of the caissons. A large void in the caisson's core was discovered, due to a faulty but widely used method of construction. The delay proved ruinous for the developer, but without Khan's resolution catastrophe could have occurred.

Andrew Saint reviews Yasmin's book "Engineering Architecture: The Vision of Fazlur R. Khan"

The building was named after John Hancock who was a merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that the term "John Hancock" became, in the United States, a synonym for signature. And true to his memory, the Fazlur Rahman Khan-designed X-brace giant became a symbol of Chicago's industrial might.

John Hancock (12 Jan 1736 / 23 Jan 1737 – 8 Oct 1793)

John Hancock (12 Jan 1736 / 23 Jan 1737 – 8 Oct 1793)

The inward-sloping shape not only created a strong skyline image, but also served the building's functional needs by providing big floors on the bottom for offices and parking, and smaller floors above apartments (later condominiums).

The X-braces had other aesthetic advantages.

They broke down what could have been an oppressive mass into a series of parts that, while not human-scaled, were nevertheless far less monolithic than the uninterrupted exterior columns of the Amoco Building. The end result was a giant but almost playful work of abstract art. Adults and children alike have portrayed the building as a cartoon-like series of stacked X's.

Before the Hancock went up, North Michigan Avenue largely resembled a Parisian boulevard of elegant low- and mid-rise neoclassical buildings. After the tower shattered that fragile scale, the avenue became an urban canyon of hulking blockbusters.

The tube-like structures that undergird the twin towers of New York's World Trade Center (finished in 1972 and 1973), Chicago's Amoco Building (1973) and Sears Tower (1974) all are indebted in some respect to the Hancock. Yet what sets the Hancock apart from these other giants is the way the leaders of Skidmore's design team - architect Bruce Graham and the late structural engineer Fazlur Khan - expressed the building's bones to create an instant skyline symbol.

As Graham once explained, "It was as essential to us to expose the structure of this mammoth (building) as it is to perceive the structure of the Eiffel Tower, for in Chicago, honesty of structure has become a tradition".

Blair Kamin of Chicago Tribune

The concept minimised the use of steel, saving an estimated $15 million, and allowed the Hancock building to reach the then-staggering height of 100 stories and 1,127 feet (344 m) tall. Dark, strong, powerful, it was a revolution in skyscraper design. Upon completion, the John Hancock Center became the 4th tallest office building in the world. But the Hancock is not simply an office building but a mixed-use tower that also houses retail stores, car parking, and commercial office space on the lower floors, more than 700 apartments (now condominiums) occupy floors 45 through 92 - making it the world's highest living quarters, with an observatory and a restaurant above that. It's a mini city within a building - a vertical village. It is a skyscraper where you can live, work and play. From swimming on the 44th-floor pool to even going grocery shopping (also on the same 44th floor) // nothing quite like swimming on the 44th floor

Instead of a traditional cornerstone, the Hancock has a special time capsule, once displayed in its observatory and now in storage. Among the capsule's contents: an insignia from the spacesuit of Chicago-born astronaut Eugene Cernan, two autographed baseballs, a Chicago Blackhawks ice hockey puck and a letter from the late Mayor Richard J. Daley. The time capsule may be brought out for a millennium celebration in the observatory.

The Hancock is a creature of fact, not fancy; reason, not romance; blue-collar directness, not the high life of the urban swell.

Yet like all great art, the 28-year-old Hancock, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, defies easy categorization. Indeed, the extraordinary thing about this skyscraper is the way it elevates pragmatism into poetry, though, admittedly, this is poetry on steroids - not Emily Dickinson, but Carl Sandburg.

...This new concept of urban living was made possible by a stunning synthesis of architecture [of Bruce Graham] and engineering [of Fazlur Rahman Khan].

Blair Kamin of Chicago Tribune

Soaring above the vertical malls of North Michigan Avenue, the Hancock was originally conceived as two separate buildings, one office building and one apartment building. Upon hearing that the office space would be hard to rent because the site was too far from downtown’s train stations, the project’s original developer, Jerry Wolman of Philadelphia, reduced the size of the office building and opted to place apartments on top of it. Bruce Graham and Fazlur Khan did the rest, combining blue-collar muscle and black-tie elegance in a giant truncated obelisk.

Interesting facts:

- On a clear day, you can see four states - Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin - from the 94th floor observatory.

- Building design eliminated the need for inner support beams, greatly increasing amount of available floor space.

- The design concept allows only five to eight inches of sway in a 60mph wind; tested to withstand winds of 132 miles-per-hour.

- The center occupies only 40% of site space, creating rare open space on a bustling thoroughfare.

- The outer skin of high-density black aluminum contrasts with 11,459 extra-thick, glare-proof, bronze glass windowpanes.

- The building is shaped like a wedge, creating the illusion that it is even taller. This was drafted to balance the need for extra parking/commercial space below, and, smaller residential areas above.

- Gutsy, masculine design in the tradition of industrial Chicago.

- It takes two men 40 hours each to change all the light bulbs in the Crown of Lights, on the 99th floor.

- With the nation's fastest elevators, you'll arrive at the Observatory in 39 seconds.

- Birds stop at about 500ft high so don't expect to see one eye-to-eye up here.

- If you melted all the metal in John Hancock Center you could make 96 tour buses to transport the hardest rock bands!

- The observatory has the only open-air viewing deck in Chicago. They say fast-talking politicians gave the city its nickname, but up here, you might think otherwise.

- To make the Hancock's frame, enough steel to build 33,000 cars was used. The frame took three years to complete and weighs 46,000 tons. The building is supported by caissons drilled 190 feet into bedrock.

- The building's 11,459 bronze glass window panes would create a single, 5-foot-wide sheet of glass 13 miles long. It has enough wiring to extend 1,250 miles and generates enough power to supply a city of 30,000 people.

Unlike earlier skyscrapers, in which an internal cage of steel carried most of the building’s load, the Hancock’s exterior columns, beams and X-shaped braces formed a rigid tube that did most of the heavy lifting and braced the building against the wind. The arrangement allowed the Hancock to be erected for the same cost as a conventional 45-story office building. And the stacked X-braces offered an instantly recognizable skyline image, quickly silencing detractors who had likened the Hancock to an oil derrick.

Blair Kamin of Chicago Tribune

Khan was involved in testing throughout his career, whether it was pulling a model with a string (with graduate students he advised at the Illinois Institute of Technology), testing a concrete beam in a university laboratory (for the record-setting deep beams of the Brunswick Building), or assessing the properties of a progressive structural fabric for a tensile structure (to create the tent-like roof structures of the Hajj Terminal). He was able to judge when to undertake sophisticated research, and when to devise simple tests.

A telling illustration of Khan’s insightful approach to design and testing dates to 1965, when he was working on the John Hancock Center. The engineers had calculated the anticipated sway of the 100-story tower based on their design of a trussed tube structure. But guidelines were not yet available for predicting whether this motion would cause discomfort to the building residents. Khan was pondering how to evaluate perception of building motion when he visited Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry with his family one Sunday. Standing on the large rotating platform of a washing machine exhibit, he realized that the platform could serve the purpose. He conceived a means of testing subjects, who stood, sat, or lay on the platform as he varied its acceleration, and assessed their responses. Based on the results, together with those from another simple test, he was able to predict that most occupants would not experience discomfort in strong wind.

In 1999, there was fresh confirmation of John Hancock Center's genius when it won the American Institute of Architects’ prestigious "Twenty-five (25) Year Award". The award, handed out since 1969, is annually conferred upon a design of enduring significance that is 25 to 35 years old. Nearly all of the previous winners can be found in the art history books, among them Frank Lloyd Wright's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's 860 and 880 North Lake Shore Drive Apartments, which in many respects are the Hancock's inspiration with their austere yet elegant, skin-and-bones design.

One quiet Sunday afternoon in 1968, when a former architecture student of his from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Phyllis Lambert, was visiting along with her nephew, my father took all of us to the top of the John Hancock Center (the structure was nearly complete; residents started moving into the building the following year).