BAKSAL

Sheikh Mujib becomes President again and develops one-party system

As the situation got worse and Sheikh Mujib became more isolated, on 28 December 1974 he declared a state of emergency and on 25 January 1975 he declared himself fourth president of Bangladesh through a constitutional amendment, against the private sentiments of the majority of the members of parliament belonging to the Awami League. The amendment provided that "Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the Father of the Nation" would be the President of the country for 5 years from the date of the constitutional amendment. Muhammad Mansur Ali, the Home Minister, replaced him as the new Prime Minister. Sheikh Mujib soon established a system of one-party rule to move from democratic parliamentary governance to autocratic presidential ruling.

The 4th Amendment to the Constitution specified that when the National Party is formed a person shall...

- In case he is a member of Parliament on the date the National Party is formed, cease to be such member, and his seat in Parliament shall become vacant if he does not become a member of the National Party within the time fixed by the President.

- Not be qualified for election as President or as a member of Parliament if he is not nominated as a candidate for such election by the National Party.

- Have no right of form, or to be a member or otherwise take part in the activities of any political party other than the National Party.

The constitutional amendment bill was passed without any reading and discussion in parliament, since the normal rules of procedure of the House were suspended, and the whole process of amendment was completed within half an hour. Thus "the single-party power was seized, not granted by voters".

Thus, Sheikh Mujib's catch-all legislation completely shut out all opposition. No one could engage in any form of politics without being a member of the National Party. And the National Party's membership, according to the Party's constitution, could only be obtained with the consent of the Chairman, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Only the National Party, i.e. Sheikh Mujib, would decide who would be candidates for election and voters would make their choice from among those selected by him.

I shall nominate one, two or three persons for contesting a seat in Parliament. People will choose who is good or bad.

BAKSAL - the 'Second Revolution'

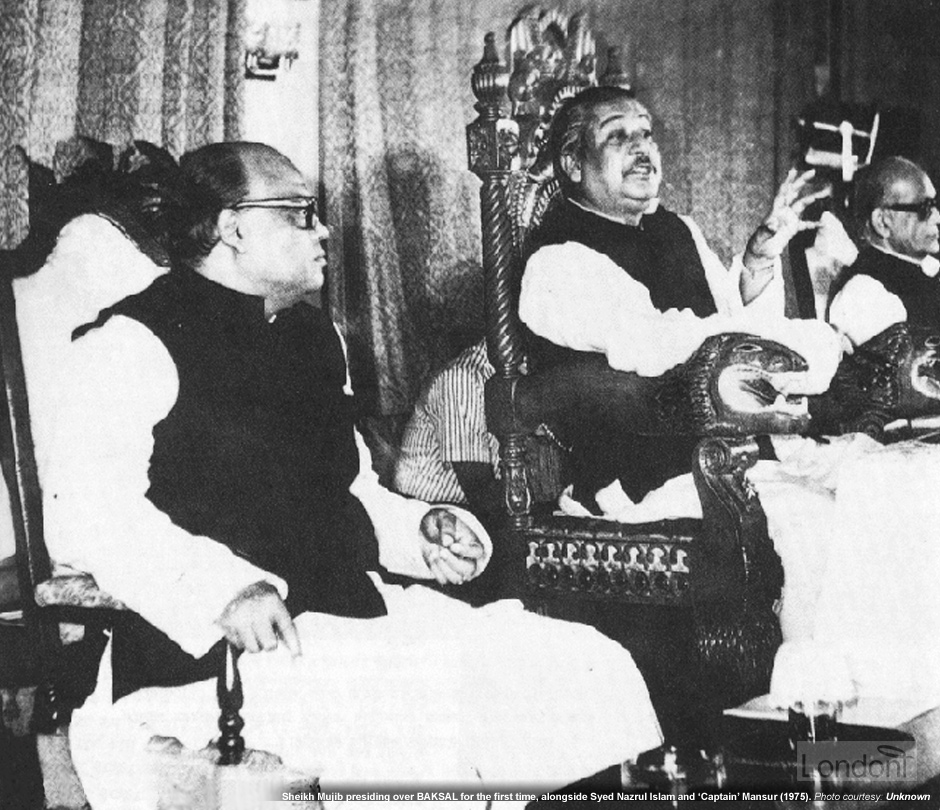

On 7 June 1975 Sheikh Mujibur Rahman achieved what to him was the crowning glory of his administration - the formation of Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (Bangladesh Farmers and Workers Awami League), or BAKSAL for short. Declared as a 'Second Revolution', BAKSHAL (pronounced Bakshal) was established following the Fourth Amendment (Article 117A) to the Constitution of Bangladesh and by merging (Bangladesh) Awami League and Krishak Sramik Party (Peasants' and Workers' League). It also contained pro-Moscow Communist party of Moni Singh and the National Awami Party (NAP) of Muzaffar Ahmed.

The pressure of the radical opposition, constant prodding by Sheikh Fazlul Huq Moni, Mansur Ali and other pro-Moscow leaders, and Mujib's own proclivity for total power and his desire to subordinate the administrators (most of whom had been recruited by Pakistan) to his party cadres, all propelled Mujib into the decision to introduce a one-party system.

BAKSAL was formed as the new "National Party" and all other parties were banned. The President was authorised to suspend the activities of all political groups that refused to join the "new" party. Government civilians were ordered to join this sole 'legitimate' party which superseded the Awami League and became the only party in a single-party state. Out of the eight opposition members in the Jatiyo Sangshad (Parliament) four joined BAKSAL.

Despite Sheikh Mujib's repeated appeals to all parties to join BAKSAL, the radical parties - that is Jatiyo Samajtrantric Dal (JSD) led by Serajul Alam Khan (who founded the Nucleus during Muktijuddho), Purbo Bangla Sarbohara Party (East Bengal Communist Party) whose leader Siraj Sikdar had been arrested and klled in the first week of January 1975, Purbo Bangla Sammobadi Dal-Marxbadi-Leninbadi (East Bengal Communists Party-Marxist-Leninist), the East Pakistan Communist Party-Marxist-Leninist, and the Bangladesh Communist Party (Leninist) - abstained from joining. The pro-Moscow factions, of course, hailed the formation of the BAKSAL. But only a few of their leaders were included in the party's 115-member Central Committee.

The Awami League is the natural leader of the War of Liberation yet after the liberation Awami League owned the War of Liberation'71 whole-heartedly with the purpose of becoming its sole agent. In the process, it not only ignored the contribution of others but also made constant endeavour to discourage them to own the War of Liberation.

The anti-establishment attitude of yesterdays with imaginary images of Ayub-Yahya remained predominant, as a result people in power were suspicious of civil and military bureaucracies without realising that the entire political scenario had been completely changed through the long political struggle culminating in the Liberation War.

Executive Committee

On 7 June 1975, President Mujib, the BAKSAL chairman, announced the formation of a 15-member Executive Committee, a 115-member Central Committee, and five sister organisations - Jatiya Krishak League (with Phani Bhushan Majumdar as General Secretary), Jatiya Sramik League (Professor Yusuf Ali), Jatiya Mahila League (Sajeda Choudhury), Jatiya Juba League (Tofail Ahmed) and Jatiya Chhatra League (Sheikh Shahidul Islam). All members of the executive committee were nominated by Sheikh Mujib and were to enjoy the status of ministers.

The Executive Committee of BAKSAL was made up of the following members:

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman () Self-appointed new President of Bangladesh after Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of Bangladesh. Founded BAKSAL on 7 June 1975.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman () Self-appointed new President of Bangladesh after Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of Bangladesh. Founded BAKSAL on 7 June 1975. Syed Nazrul Islam () Vice President of BAKSAL.

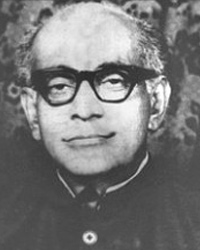

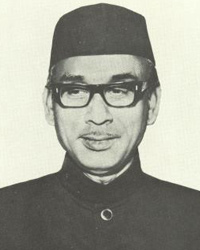

Syed Nazrul Islam () Vice President of BAKSAL. Muhammad Mansur Ali () Replaced Sheikh Mujib as Prime Minister.

Muhammad Mansur Ali () Replaced Sheikh Mujib as Prime Minister. Khandaker Moshtaque Ahmed ()

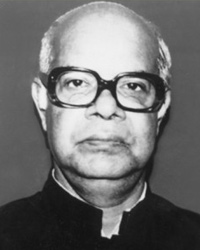

Khandaker Moshtaque Ahmed ()  A. H. M. (Abdul Hasnat Mohammad) Qamaruzzaman ()

A. H. M. (Abdul Hasnat Mohammad) Qamaruzzaman ()  Abdul Malek Ukil ()

Abdul Malek Ukil ()  Prof. Yusuf Ali ()

Prof. Yusuf Ali ()  Manaranjan Dhar ()

Manaranjan Dhar ()  Mohiuddin Ahmed ()

Mohiuddin Ahmed ()  Gazi Golam Mostafa ()

Gazi Golam Mostafa ()  Zillur Rahman ()

Zillur Rahman ()  Sheikh Fazlul Huq Moni ()

Sheikh Fazlul Huq Moni ()  Abdur Razzaq ()

Abdur Razzaq ()

The General Secretary of the five sister organisations were (including Prof. Yusuf Ali above):

Phani Bhushan Majumdar ()

Phani Bhushan Majumdar ()  Sajeda Choudhury ()

Sajeda Choudhury ()  Tofail Ahmed ()

Tofail Ahmed ()  Sheikh Shahidul Islam ()

Sheikh Shahidul Islam ()

This Supreme body of BAKSAL were close followers of Sheikh Mujib and, with one exception, prominent leaders of the former Awami League. The General Secretaries and a majority of the members of the Executive Committees of the five wings of the party nominated by Sheikh Mujib were all former leaders of the Awami League and Awami League-affiliated labor, student, youth, peasant and women's organisations.

An analysis of the composition of the various committees thus showed that BAKSAL was in fact the Awami League under a different name.

Mujib was accused of surrounding himself with sycophants, of allowing relatives to enrich themselves, of not consulting others and of scapegoating colleagues when threatened by public discontent. The expulsion from his cabinet of Tajuddin Ahmad, a former Prime Minister who was regarded as incorruptible if also pro-Indian and pro-Soviet, gave offence to many.

Greedier Awami League politicians flourished and the party as a whole was increasingly seen as timing for 'autocratic dominance'. At one stage MAG Osmani, who had led the Mukti Bahini, seems to have told Mujib: "I have watched Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan and don't want you changed into Mujibur Rahman Khan". But his remark was an exception. Most of Mujib's Awami League colleagues refrained from questioning him.

The Mujib government had already demonstrated its bent toward civil dictatorship by, among others policies, banning politico-religious parties, evicting the communists who rejected the Delhi-Moscow axis and, eventually, creating a one-party system. This system was based on a political organization which was no longer the AL (Awami League), but a much more authoritarian core composed of Mujib's relatives and close associates, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (People's League of Bangladesh's Peasants and Workers – BAKSAL).

Most of the civil society's organizations, which had made the 1971 mobilization possible, were considerably weakened. This authoritarian drift yielded one serious consequence: the only genuine opposition to civil dictatorship came from the army.

Jérémie Codron, Analyst

District Governors

A week after the formation of the Executive Committee, on 22 June 1975, it was announced that the existing 19 districts of Bangladesh would be divided into 60 new districts to ease administration. This was achieved through a Presidential Ordinance. These new districts would come into operation from 1 September 1975, and each district will be ran by a District Governor. These governors, who were handpicked by President Mujib himself, were announced on 16 July 1971 and were made up of 33 MPs, 13 civil servants, an army officer, lawyers, politicians and tribal chiefs.

The governor-designates were given a 27-day special political training starting on 21 July 1975 and expected to finish on 16 August 1975 (which ironically became the day after Sheikh Mujib's assassination). The plan was to place half a battalion of the Jatiyo Rakhi Bahini (JRB) - recruits drawn mainly from organisation affiliated with Awami League - under each governor, while the governors were to be directly under the control of President Sheikh Mujib. It was further planned that the JRB units would be increased annually so that by the end of 1980 the total strength of what was in fact a party militia would be 130,000. One regiment of JRB would then be placed under the command of each governor.

The District Governors were tasked with:

- Looking after law and order.

- Development works.

- Ensuring proper distribution of goods coming from abroad.

- Allocating money for works programmes.

- Formulating family planning schemes.

- Publicity.

- Overseeing production. They would see whether the harvesting of paddy has been made or not, whether interest is taken by mothers and your to stop corruption in the thanas.

- Controlling Bangladesh Rifles (the para military border security force), the Rakkhi Bahini, police and army units stationed in their areas.

Such a scheme of local government was a complete departure from the colonial and post-colonial systems that Bangladesh had inherited. It was felt that the district governor system would destroy the vestiges of the exploitative colonial bureaucracy and bring the administration closer to the people and make independence politically and economically meaningful to them. BAKSAL also envisaged large scale nationalisation of private concerns with a view to eliminating social and economic inequalities and exploitations.

They [the District Governors] were to be the President's hands, feet and mouth and were expected to work closely with the 61 Baksal District Secretaries who would be the Party Chairman's [i.e. Sheikh Mujib's] eyes and ears. These too would be nominated by him. In every case Sheikh Mujib's criterion for selecting people for these posts was, as he publicly admitted, "because they are good to my eyes".

The BAKSAL Committee members and district governor-designates were selected by Sheikh Mujib, Sheikh Moni, Abdur Rab Sarniabat (a Minister in Mujib's Cabinet, Mujib's brother-in-law and Sheikh Moni's father-in-law) - the hard-core of the political elite since Sheikh Mujib's return to Bangladesh in January 1972. As time passed, the BAKSAL leaders began to equate the party with the state. It seemed obvious that the new system of "copying the Soviet methods but rejecting its ideology" was designed to suppress every vestige of opposition and perpetuate the corrupt rule of the "Sheikh Mujib Tribe" in the "softest" state in the world.

These non-elected "Governors" were to control the Bangladesh Rifles, the Rakkhi Bahini, police and army units stationed in their respective areas from 1 September 1975. Thus the man who led his country towards independence and freedom, within four years after its independence turned it into a monolithic and one party state.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman gave a variety of reasons for creating this tight chain of command. When the 4th Amendment was passed by the National Assembly he said the one-party system was intended to implement the four State Principles - nationalism, democracy, socialist and secularism. Later, at a public meeting in Dhaka on 26 March 1975 - on 4th anniversary of Independence - Sheikh Mujib spoke about "four plans" being the basis of BAKSAL.

Number one plan is to eliminate corrupt people. Number two is to increase production in fields and factories. Number three is population planning and number four is our national unity.

Mujib's many reasons for Baksal are not contradictory, and it could be argued that they were the facets of a radical reform of national life. But was reform what he really intended? If indeed that was his purpose then he had a curious way of going about it. In the first place he never lacked authority. Even as Prime Minister in a Westminister-style government his towering position as Bangabandhu would have allowed him to enforce any reform he desired. Had Mujib wanted he could have sent the whole Cabinet, Parliament and Civil Service packing and replaced them with persons of his choice.

Secondly, the personnel appointed to flesh out Baksal were the same grasping Awami Leaguers and civil servants whose incompetence and corruption had helped to bring Bangladesh to the brink of collapse. There was nothing to indicate that they had changed their ways. Thirdly, Mujib himself had not changed his style. He still confused platitudes with policies as though they were enough to conjure away the crises. And when all is said and done, Mujib's talk about removing "oppression, injustices and repression" begs the question: Whose? Since the State's founding the people had known no other government than Sheikh Mujib's. It could therefore be correctly assumed that he was responsible for all the terror and the rot which he now professed to reform by the 'Second Revolution'.

All this makes clear that Baksal was another one of Mujib's political games and reform was not the objective. Baksal was intended to shut out all opposition and give him a stranglehold on the country. He would have achieved this ambition on 1 September 1975 had he lived.

In order to control the media, the government banned all the newspapers except the government-run newspapers, the Bangladesh Observer and the Dainik Bangla, via the News Paper Cancellation Act on 16 June 1975. It also took over the publication of the Daily Ittefaq and the Bangladesh Times.

His declaration of one party rule was opposed by many political opponents, and corruption started to spread during those initial years of Bangladeshi independence.

In short, BAKSAL, as a system, aimed at achieving an exploitation-free and socialist economic and administrative order more or less close in spirit and contents to the systems of government in contemporary socialist countries.

The new system, in fact, created a lot of misgivings and revulsion amongst the bureaucracy, army, and civil society. Many of the people who had supported Bangabandhu for his role as a democratic activist, were unhappy to see him as the champion of an authoritarian single party system.

Sirajul Islam, historian