'Muktir Gaan' documentary

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

Muktir Gaan (Songs of Freedom) is a 90-minute long documentary film which takes the audience back to 1971 and explores the impact of cultural identity on the liberation war, where music and song provided a source of inspiration.

For large part, it follows a group of young Bengali cultural activists known as the Bangladesh Mukti Sangrami Shilpi Shangstha (Bangladesh Freedom Struggle Cultural Squad) who traveled through refugee camps and battle zones performing rousing patriotic songs and political puppet shows to inspire the freedom fighters and increase the bond amongst the whole emerging nation.

The original video footage was captured by American film-maker Lear Levin. Bengali director Tareque Masud and his American wife Catherine Lucretia Shapere (later Catherine Masud) made ample use of this footage and combined it with archived photo and videos of the war from around the world to produce Muktir Gaan. They used footage from CBS and NBC in New York, ITN, BBC and Visnews in London, and shots from Sukdev's documentary "Nine Months to Freedom" and Gita Mehta's "Dateline Bangladesh" as produced by Bombay Films Division.

The Masuds directed and scripted the documentary whilst Catherine, assisted by young student Dina Hossain, carried out the editing and Tarik Ali provided the narration.

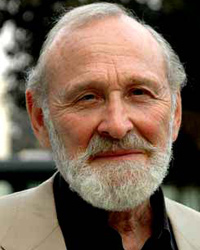

Lear Levin ()

Lear Levin ()  Catherine Masud (née Lucretia Shapere) ()

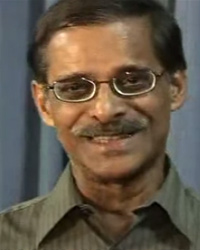

Catherine Masud (née Lucretia Shapere) ()  Tareque Masud ()

Tareque Masud ()  Dina Hossain ()

Dina Hossain ()  Tarik Ali ()

Tarik Ali ()

Twenty-five years in the making, the film began with the ambition of Lear Levin to make an epic documentary on the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 in the tradition of Robert Joseph Flaherty, a fellow American filmmaker who directed and produced the first commercially successful feature length documentary film, 'Nanook of the North' (1922).

Levin, then a 30-year-old young man who knew no Bengali, and his crew followed the troupe of traveling musicians who sang songs of struggle to inspire the guerrilla cadres and the millions of refugees. There's also footage of the crew's interaction with the Freedom Fighters during a brief visit to a liberated zone in late November, and Lear's beautifully shot pastoral images of rural Bengal - farming, bathing, people going to market, cow carts, river scenes.

After the Pakistani army's crackdown, I wanted to inform the world community about the atrocities of the occupation army. And to do so, I decided to make a documentary film titled 'Joy Bangla'. My aim was to make a comparison between the post and pre-war situation in this land.

Places that were covered with green trees and structures were seen barren after the Pakistan army's invasion.

...Another aspect of Lear's footage had an exceptional quality of timelessness. These were the numerous close up portraits of ordinary Freedom Fighters: listening to the troupe's music, caught in the rain, or just standing by the roadside. No typical news cameraman would or could have taken portraits of such startling perception.

However, these latter scenes were not included in Muktir Gaan as the Masud's wanted to appeal to a new generation of young, contemporary Bengali audience who are more likely to be disinterested in the liberation struggle.

Muktir Gaan features a total of 11 immortal songs sung by Mahmudur Rahman Benu, Shahin Samad, Tarik Ali, Laila Khan, Lubna Marium, Swapan Chowdhury, Bipul Bhattacharjee, Sharmin Murshid, Dulal Chandrashil, Lata Chowdhury and Debobroto Chowdhury. The artistes of Bangladesh Mukti Shangrami Shilpi Shangstha wrote their own songs and drew pictures to inspire the FFs and the general people with the spirit of liberation war.

The film also features Brigadier General (retired) Giasuddin Chowdhury, Aminul Haque Badshah and other nameless freedom fighters who fought for liberation of the country.

Lear captured the spirit of the Bengali people through 20 hours of beautifully photographed footage. However, he became so caught up in filming that he returned to the US only just as the Bangladesh war was coming to an end. He was unable to get funds to complete his 'Joy Bangla' project and, disheartened by lack of interest, he shelved the project, literally, on the walls of his basement in New York - not to be seen for the next 20 years.

By the time Levin returned with over 20 hours of footage from India and Bangladesh, however, the media and the public had moved on. Cambodia, Watergate, the continuing struggle in Vietnam and a host of other events merged to make the obsession with Bangladesh a short-lived moment in the history of media frenzies.

After Tareque and Catherine Masud married in 1988, they moved to Staten Island, New York, and eventually tracked down the 20-year-old trail of Levin.

It was in the fall of 1990 that the directors tracked Levin with the intention of making a film based on his material.

In New York, Tareque was working in a famous used-book store called The Strand, and amassing an enormous collection of books on film and Indology in the process. I was an executive in an advertising agency, half-heartedly climbing the corporate ladder. We were both looking for something inspiring to throw ourselves into, but weren't quite sure how and where to start.

At that time, we were spending almost every weekend with my brother Alfred, who was completing his post-doctoral work in physics in Princeton, New Jersey. One day he was stopped on the street by a South Asian-looking woman who needed directions to the physics department. They began to chat - she said she was originally from Bangladesh, and Alfred said his sister was married to a Bangladeshi.

One coincidence led to another, and it turned out she was the wife of Tarik Ali, an old friend of Tareque's first cousin Benu. The Alis lived in the neighbouring town of Lawrenceville, and the following weekend found us sitting cozily in Tarik bhai's living room, exchanging stories of Dhaka and dreams of return.

The conversation drifted to the Liberation War. Tarik bhai and Tareque's cousin Benu bhai were together at that time, singing in a cultural squad of refugee artistes. Tarik bhai recalled that an American film-maker and his crew had traveled with them for some time, documenting their experiences during the war. Tareque vaguely remembered that in the early 1970s, Benu bhai had often mentioned this film-maker in passing during reminiscences of the war. His name, according to Tarik bhai, was Lear Levin. We were immediately intrigued. What an unusual name: Lear. It conjured up images of grandeur and tragedy. What had become of his footage? Perhaps it was a journalistic catalogue of events of the war. Certainly Lear no longer lived in New York. Perhaps he was long since dead.

Over the next week or so, Tareque and I gradually forgot about Lear Levin. But the following Saturday, I was suddenly inspired to pick up the phone book and look through the Ls. There were pages and pages of Levins. But suddenly, there it was. Lear Levin. And Lear Levin Productions. I am always nervous about phone calls, so I handed the phone to Tareque. He called the production office -- it was the weekend, but he could leave a message. But someone picked up the phone.

Tareque: Yes, I was trying to reach a Mr. Lear Levin.

Lear: This is Lear Levin.

Tareque: Oh ... were you by any chance in Bangladesh in 1971?

Lear: Yes.

Tareque: You did some shooting then?

Lear: Yes.

Tareque: Well, I wanted to talk to you because I'm also from Bangladesh, I'm a film-maker, my name is Tareque Masud.

Mahmoodur Rahman Benu is my first cousin. Do you remember Benu?

At the sound of Benu's name, Tareque could almost feel, through the telephone line, a rush of emotion overtaking Lear.

Lear: Of course I remember him. Well, in 1971 I was a young man, 30 years old. I went to Bangladesh to make a film about the Liberation War. I put a lot of myself into that film, a lot of money and time, but eventually I had to abandon the project. And now, you have called. I've been waiting almost 20 years for this phone call.Catherine Masud recalls her and her husband Tareque's search for Lear Levin,

Not long after a telephone conversation with Lear Levin, the Masuds met him at Film Video Arts, a film-maker's cooperative in Lower Manhattan where Lear brought along a couple of cans of his footage. Much to Tareque and Catherine's amazement the editing machine began to play back pristine, full colour images rather than dusty, black-and-white newsreel as they were expecting. Upon seeing his cousin (brother) Benu and many other familiar faces from his childhood, 'all fresh and glowing with youth and the ideals of '71', Tareque nearly began to cry. Lear then informed the couple that he had another 19 hours of footage still lying in his basement.

A few days later, the Masuds went to Lear's home on the upper West Side of New York City to begin the lengthy process of studying and cataloging his footage. In the basement Tareque unearthed the old boxes stuffed with 91 rolls of movie films of over 36,000 feet with a total duration of almost 20 hours, a never-seen-before documentary on the birth of Bangladesh.

His basement was not the dusty dumping ground typical of many homes; it was the storage centre of a professional film-maker, and as such, was professionally maintained. It was clean and cool and the walls were lined to the ceiling with shelves of film cans and boxes. He pointed to one particular wall and there we saw a series of cardboard boxes unobtrusively stacked for posterity. They all bore a distinguishing hand written label: "Bangladesh".

Not only did the Masuds find Levin, they also received permission to use the footage without any royalty. Compared to the exorbitant prices the filmmakers had to pay for the few minutes of archival news-reports obtained elsewhere, Levin's gift made the film possible.

A process of reverse script-writing began, with the Masuds extracting sequences from 20 hours of footage to piece together the story of a traveling band of Bengali musicians collecting funds for the war effort and raising the spirits of the guerrillas. Along the way, the husband-wife team found assistance from a variety of activists in the Bengali community in the US, including invaluable help in raising the seed money from fund-raisers. For a community that was struggling for economic stability in the US, being instrumental in a large-scale film project was unusual at that time.

It took five years to complete the film. Despite opposition by the BNP-led government - the film contains Sheikh Mujib's 7th March speech, shots of soldiers yelling his name, reference by Ziaur Rahman to Sheikh Mujib as "great national leader" during the Declaration of Independence - and attempts to block it for giving 'partisan version of history' , the movie was premiered in Dhaka on 1 December 1995.

Muktir Gaan was a resounding critical and commercial success, and won the National Award for best documentary (1996) as presented by Bangladesh Film Journalists Association, as well as a Special Jury Prize at Film South Asia '97, Kathmandu.

Section of Lear Levin's original footage that was left out from Muktir Gaan, such as life in the refugee camps, refugee women cooking, children fetching water and bathing, people receiving rations, refugee children being inoculated, etc, were used extensively in the Masud's next venture - 'Muktir Kotha' (Words of Freedom). Released in 1999, this 80-minute documentary continues the story after 1971 when those who fought for freedom were still living in poverty whilst the rewards were reaped by the rich. The ethnic and religious minorities, women and others who are marginalised, tell their own stories of genocide, rape and other atrocities.

'Ekkattorer Shobo Shainik'

The mammooth efforts of Belal Mohammad and others behind the formation of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra has been captured in a documentary entitled "Ekkattorer Shobdo Shainik" (Voice Warriors of '71). It is made by Sajal Khaled and Kawser Mahmud and tracks the history of the Bangladesh's first radio station from its inception through the nine moths of its early existence.

Sajal Khaled ()

Sajal Khaled ()  Kawser Mahmud ()

Kawser Mahmud ()

Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra was the first organised group venture by the people to fight for what they believed in. It was an organization that was conceived as a means of great requirement during that moment, and was ended and shifted to something new, after having served its purpose.

Painters like Dey Das Chakraborty, Kamrul Hasan, Nazir Ahmed, Nitin Kundu, and Pranesh Mandal also played an important role.