Archiving long lost memories

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

Like any other artefact, photography also has an aesthetic value. That is why preservation of photography is so important. For more than two decades Shahidul Alam, internationally acclaimed photographer, writer, and human rights activist, has made it his mission to collect Muktijuddho-related photos, visiting the photographers in their homes and saving their negatives.

By highlighting the images taken by these accidental archivists, the curators have created an intimate, reflexive portrait of the war, ranging from photographs that are well known to others that have never been seen in public.

Thirty five year ago, even longer perhaps, just a camera in hand, they had gone out to bring back a fragment of living history. Today, those photographs join them in protest. Peering through the crisp pages of the newly printed history books, they remind us, "No, that wasn’t the way it was. I know. I bear witness".

The black and white 120 negatives, carefully wrapped in flimsy polythene, stashed away in a damp gamcha [cloth], have almost faded. The emulsion eaten away by fungus, scratched a hundred times in their tortuous journey, yellowed with age, they bear little resemblance to the shiny negatives in the modern archives of big name agencies. They too are war weary, bloodied in battle.

So many have sweet talked these negatives away. The government, the intellectuals, the publishers, so many. Some never came back. No one offered a sheet of black and white paper in return. Few gave credits. The ones who risked their lives to preserve the memories of our language movement, have never been remembered in the awards given that day.

35 years ago, they fought for freedom. They didn’t all carry guns, some made bread, some gave shelter, some took photographs.

Shahidul Alam on Abdul Hamid Raihan's preserved negatives (2007)

In 1989, Shahidul Alam co-founded Drik Picture Library along with writer and anthropologist Rahnuma Ahmed. Drik, a Sanskrit word refering to vision, inner vision and philosophy, is an award winning picture library based in Dhaka which also provide media services including web development, video production, print production and exhibitions. In 1998 Drik set up Pathshala: The South Asian Institute of Photography and Chobi Mela, the first festival of photography in Asia.

Shahidul Alam ()

Shahidul Alam ()  Rahnuma Ahmed ()

Rahnuma Ahmed ()

"The Birth Pangs of a Nation" (2011)

In 2011 Shahidul Alam published an award-winning book of photographs from the 1971 conflict with the help of Robert Pledge of Contact Press Images. Titled "The Birth Pangs of a Nation" and financed by the United Nations, the book features many of the national and international photographers mentioned above. Salil Tripathi wrote the sole essay in the book.

This year is the 40th year of Bangladesh's independence. But it also coincides with the 60th anniversary of the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, as well as the 50th anniversary of the 1961 United Nations Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, that together have provided a strong international legal framework for the protection of refugees and stateless people around the world. Since achieving its own independence 40 years ago, Bangladesh has brought many unique and compelling perspectives to the global experience of migration, forced displacement and protection of refugees and stateless persons. With the support of the government and the people of Bangladesh, the UNHCR and its sister agencies of the UN and a number of national and international NGOs have provided the assistance the refugee needs.

The images in this volume capture, in frozen frames, the hopelessness and despair of the displaced of one tragic upheaval. But it is not an unremitting saga filled with pathos. The birth of a nation is a matter of joy, and this beautiful land celebrates that, with its swaying paddy, windswept skies, the cheerful boatmen singing soulful songs in its rivers, the ecstasy of the Baul singers, the babble of its cities, the reflective calm of the countryside, and the haunting, elemental mangroves. The refugees longed for that sense of normalcy – and you see it in the curious eyes of the child looking at the new world, in the expectation on the faces of crowds standing with quiet dignity for their turn at the rations, in the joy of an impromptu volleyball match.

Extract of Salil Tripathi's essay in "The Birth Pangs of a Nation" (2011)

A film by the same name was created to accompany the book. The film, conceptualised, researched and narrated by Shahidul Alam and directed by Shuman Shams, contains personal interviews of photographers, freedom fighters, refugees and care givers, and records the pain and sacrifice of ordinary Bengalis.

1971. '71. Ekattor. Is it a number? A word? A history? To any Bangladeshi, it embodies the pride of our nation, the struggle for our independence, the pain of loss, the humiliation of being violated, the joy of victory.

The events leading up to '71 were documented almost entirely by local photographers. It was a story that international media neither knew nor was interested in. The crackdown in the night of the 25th March went barely recorded. For local photographers it was too dangerous to be out there with a camera. A few foreign journalists managed to sneak out or film through the windows of Hotel Intercontinental. They provided the only tangible record of those fateful hours. Others, who recorded those moments, were amateurs who took exceptional risks in preserving the only visual records of the atrocities.

Missing are the subtle nuanced observations of ordinary people, trying to survive, the euphoria and hope of an expectant nation being replaced overnight by the terror of living under occupation. Missing also are photographs that should be here, yet are not, by photographers who have passed away, their archives untraceable. Images have been lost. In once instance the photographer, unwilling to hand it over to a nation not concerned enough to preserve the most heroic moments of its history, hurt and impoverished, destroyed his negatives.

An incredible list of talented and deeply dedicated photographers responded to one of the greatest humanitarian crises of recent times. Their documents are an indictment of those who caused the pain, and the ones who let it happen. It is a tribute to those who abandoned all for the sake of greater good.

Has '71 indeed brought liberation to the women and men who toil on our land? To the garment workers and migrant labourers who bolster our economy, but struggle to meet basic needs. Does ’71 only mean freedom for some?

The preservation of these documents remains of crucial importance. Memories and emulsions both fade with time. We owe it to future generations to retain what exists of the only material evidence of our glorious past. We need them to remind the world. "Never, no never again".

Shuman Shams ()

Shuman Shams ()  Salil Tripathi ()

Salil Tripathi ()

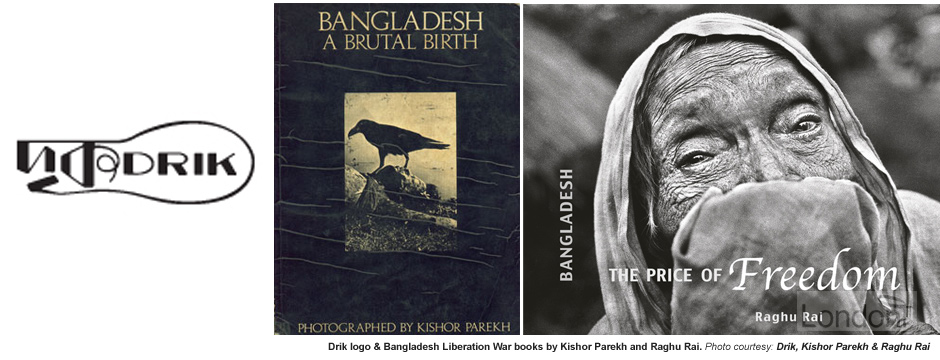

"Bangladesh: A Brutal Birth" (1972) and "Bangladesh: The Price of Freedom" (2011)

In 1972, barely few months into Bangladesh's independence, Kishor Parekh published his iconic photographs in a book titled "Bangladesh: A Brutal Birth". The 95-pages long book was a landmark document on the atrocities committed by the Pakistani forces and the suffering of the native Bengali population. Such was the powerful images captured by Kishor Parekh that the Indian government commissioned 20,000 copies of the book to raise awareness of the war. Kishor Parekh's work appeared in numerous national and international publications including National Geographic, Paris Match, Sunday Times, Time magazine, Stern, Popular Photography and Asahi Graphic.

[Kishor] Parekh, much senior to [Raghu] Rai, also covered the conflict and along with war photographer Don McCullin depicted the war in all its horror. Their photographs dripped with violence and blood at its graphic best.

Bangladesh was Kishor's highest point. Self-assigned, self-funded, driven by his own instincts, emotions and guts, in a two week period he produced a startling set of images that became a powerful book and statement.

A photograph is not just a story about a subject, it also reveals something about the person behind the lens. In barely a few days, Parekh had a comprehensive body of work, one that he was confident enough could hold together not just as a photo story for a newspaper but for an entire book. His photos of Bangladesh in the making, considered his best, are now iconic images imprinted on the minds of those who have seen them, even though the book is no longer in print. A young girl stopped short by the sight of a mutilated corpse on the road, her pursed lips seemingly swallowing a scream, her unblinking gaze unable to turn away from the horror of it. A wounded boy, naked chest down, crying as blood from his head gushes down his legs on to the road. The brutality of not just Pakistani soldiers, but India's own ("They had suffered casualties too" as Parekh's caption puts it) as they kick suspected Razakars or spies lined up against a wall, or check inside a man’s lungi - not for any sign of his religion, as this action has widely been misinterpreted as since, but for hidden weapons. Among other images, we see Mukti Bahini guerrillas as they hunt down snipers on a deserted street, Pakistani army guns piled up like firewood after their surrender, and the surrender itself: humiliation writ large on the face of Pakistan’s Lieutenant General Niazi.

Once seen, never forgotten.

In 2011, around the same time as he was publishing The Birth Pangs of a Nation, Shahidul Alam was contacted by Raghu Rai after he discovered a number of his misplaced film roles depicting the 1971 war. Raghu Rai had lost these negatives 39 years ago but his assistant stumbled upon a tightly bounded and taped envelope with 'Bangladesh' scribbled on it when they were attempting to archive a pile of his material. Luckily, the negatives were still in unblemished, 'A-class' condition.

"I never seem to find something when I need it", confesses ace photographer Raghu Rai settling behind a capacious desk at his studio in Mehrauli New Delhi. For many decades Rai had been searching for his 1971 Bangladesh war photographs and had given them up for good. But when old boxes were dug up in his studio in the process of digitizing his work, his assistance handed him a dusty old packet marked 'Bangladesh'.

"The packet was so tightly sealed that everything inside was in perfect condition", says Rai.

The packet contained Rai's first and only conflict photographs. He was barely five years old in his profession then and though some of his war photos were published in significant papers around the world, he lacked the confidence to turn them into a book.

But these photographs passed the test of time. Over the decades, the human suffering they depict is as fresh and compelling. "When I looked at the pictures today I thought they were potent enough and they deserved to be put in a book", says Raghu Rai.

Shahidul Alam excitedly contacted his network of colleagues and associates and eventually this chain reaction resulted in an unique exhibition the following year. On 7 December 2012, the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts and Indira Gandhi Cultural Center, High Commission of India, Dhaka, arranged and launched the 10-day long solo photography exhibition called "The Price of Freedom". These never-seen-before black-and-white prints, capturing the scenario at the border area during August 1971, were invaluable assets for a Bangladesh stepping into the 42nd year of freedom.

The large black-and-white and grainy images in 'The Price of Freedom'... are mainly those of refugees walking desolately, their meagre belongings wrapped in cloth bundles, into the border areas of West Bengal, Tripura, Bihar, Assam and Meghalaya. Close-up portraits of creased faces with helplessly widened eyes. Women and children, barely a single piece of tattered cloth covering their frail bodies, trudging along with nothing left to say to one another. The more fortunate, the ones evidently used to the luxury of blouses and shirts, packed together in buses and bullock carts. The next lot is of Mukti Bahini fighters, those who fought a guerrilla war against their oppressors (and with whom Rai had first crossed the border). And then of the battle fought by the Indian Army, and of the jubilation after Pakistan's surrender.

As one strolls down the gallery, he would not be able to ignore the pain and hollowness entrenched deep into the eyes of the refugees who were citizens of our very own country. One will never be able to fully empathize with what they were going through. Raghu Rai immortalized those images, one can empathize well enough.

In 2013, Raghu Rai's photographs was published in a book "Bangladesh: The Price of Freedom". However, unlike Kishor Parekh's "Bangladesh: A Brutal Birth" which focused on the gore, Raghu Rai's book focuses on the human stories. The 116-page long book contains 91 photographs, with the introduction by Shahidul Alam and short texts by Raghu Rai himself describing his two assignments during the war.

Having stored away the images for safekeeping, Rai seemed to have forgotten their whereabouts. Two years ago, he excitedly called his friend Shahidul Alam, the gifted Bangladeshi photographer, to say that the lost negatives had been found. This was a huge discovery; Bangladesh was turning 40 in 2011, and the generation that fought for its freedom was fading. Alam, who has made it the mission of his life to document the Bangladeshi saga in all its manifestations by promoting visual culture through his agency, Drik, was himself compiling the works of photographers from Bangladesh and abroad for the book he published in 2011, The Birth Pangs of A Nation. That book includes some of Rai’s photographs and went on to win an Asia Publishing Award last year. (I wrote the sole essay in that book).

Meanwhile, Rai put together his own collection, with Alam writing its introduction. The Bengal Gallery in Dhaka exhibited Rai’s photographs last December, exposing a new generation of Bangladeshis to the pain their parents’ generation had endured. I went to see the exhibition with a Bangladeshi friend. Many young Bangladeshis paused for a long time before certain images, some taking pictures on their cellphones; for many young visitors, this was their first exposure to the horrors of that war, because for long periods of the past four decades, the country has been ruled by governments that were lukewarm about independence, with coalition partners who had once been hostile to the idea of freedom from Pakistan.