Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK)

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

Following independence some workers of Bangladesh Field Hospital relocated the hospital to 132 Eskaton Road, Dhaka.

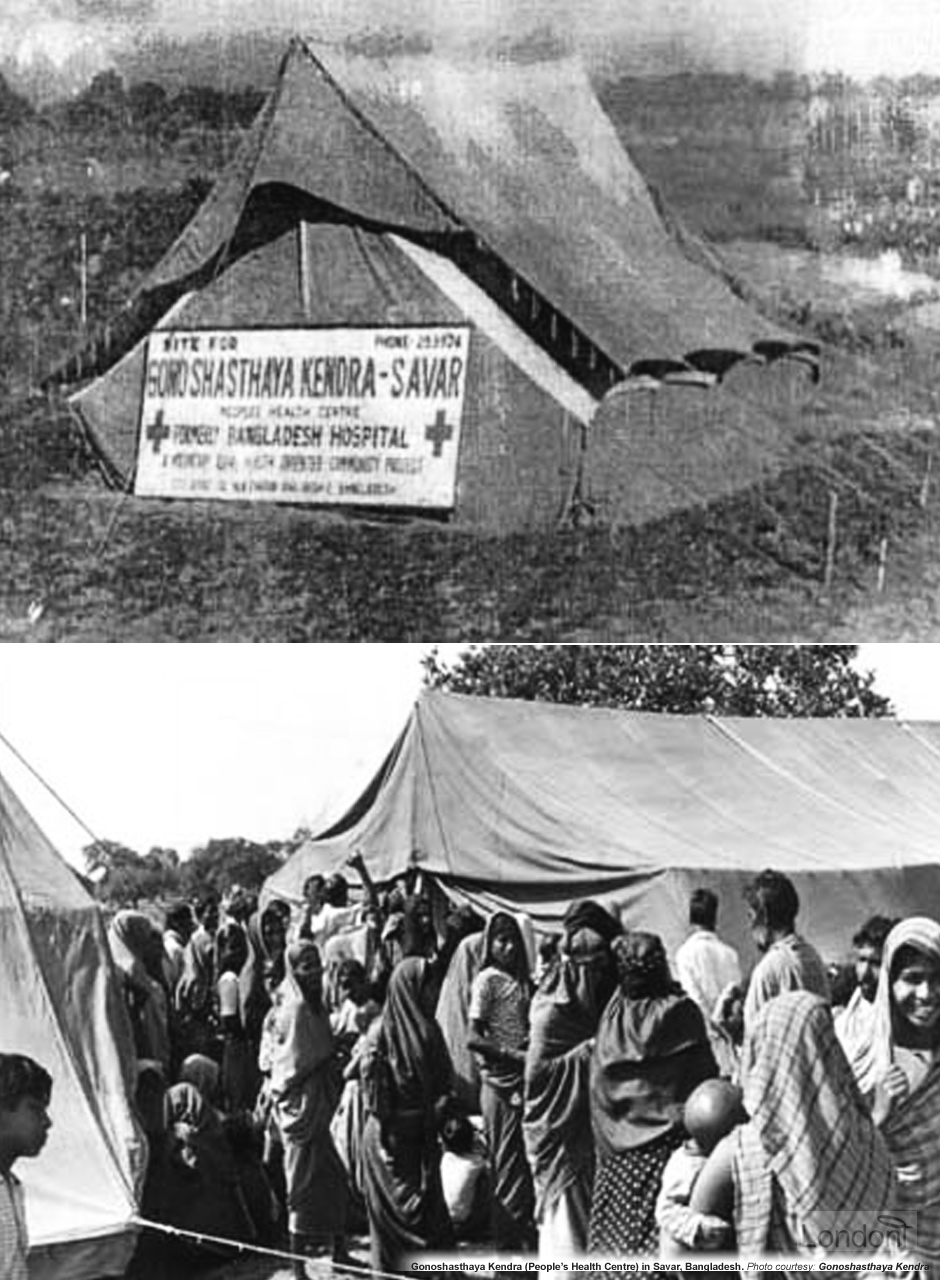

In April 1972 Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury presented a paper in Dhaka entitled "Basic Health Care in Rural Areas" which emphasised independent, self-reliant and people-orientated development. The paper provided the foundation for the establishment of a new type of healthcare system based on a holistic approach to preventing disease and which later become the basis for international discussions on Primary Health Care. In pursuit of this revolutionary vision, on 27 April 1972 the hospital moved once more, this time to the southern part of the village of Nolam, Bishmail, near the National Martyr Monument of Savar, 40 km north of the capital Dhaka. A total of 22 volunteers and doctors opened the new 'hospital' - originally just 6 large tents and an outpatient clinic under a tree which provided better health care services to the surrounding rural poor, especially women and children who became the main patients. It was opened with the motto "Grame Cholo Gram Goro" (Let us go to village and build village), and Dr. Zafrullah instigated a system whereby medical students went to educate the villagers about healthcare and, most importantly, family planning.

These barefoot doctors, as they were known, only made passing visits, and the villagers themselves were illiterate. How could they introduce concepts of birth control and leave villagers the means and know-how to use them?

The hospital was renamed as 'Gonoshasthaya Kendra' (People's Health Centre) and popularly became known as just GK. As funds became available the hospital was rebuilt in concrete.

The 1971 Swadhinata Juddho left Bangladesh with a shattered economy. Poverty was rife and the population was expanding rapidly so there was an urgent need for birth control. The lack of sanitary and health facilities also made apparent the need for a permanent rural health program. The answer was to establish Gonoshasthaya Kendra as a charitable trust with the principal objective of 'health for all'.

The lessons learned from treating the Freedom Fighters and refugees and the need to re-construct new Bangladesh provided invaluable insights in developing the vision and the characters of today’s Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK).

In the early 1970s Savar was a typical rural community without industry, a health complex or even an NGO. The post-liberation period was a euphoric time when young leaders were thinking with vision and excitement about the possible future of their communities and became eagerly involved with the task of reconstruction after the devastation wrought by the war.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra - The People's Health Centre - was born out of this idealism.

GK is a non-government organisation (NGO) and was established with two visions: firstly "the fate of the poor decides the fate of the country", and secondly "development of the country depends on development of women". To exemplify this vision, the staff chose community living and participated in morning agriculture. Local villagers also donated land and basic building materials. Later on, two other hospitals, in Shimulia and Dhaka, and sub-centres in 13 surrounding districts were established.

When peace came, he found no suitable openings for a skilled, British-trained vascular surgeon. "If I wanted to survive", he said, "I discovered that I had to do bread-and-butter surgery for the next 10 years".

Zafrullah recognisd that his country's awesome health problems could never be solved simply by curative medicine practised by a few qualified physicians. "Prevention would be much more useful than curative medicine, and certainly less expensive. And, at least so far in the future as we could see, paramedics would probably be more important than physicians". In the villages there were few licensed doctors - perhaps 1 for each 30,000 of the population. There were plenty of villagers, but turning them into paramedics presented difficulties. "Less than 2% of the women and 8% of the men were literate", he says. Even with such a handicap, he commenced a training program. In a few years he was allowing some of his young paramedics to do minor surgery, setting broken bones and performing abortions. "This made the medical mafia very nervous", he recalls. "The minister of health - he knew me, he had been one of my teachers - told me, 'Stop this or we must send you to jail!' I said to him, 'I would very much love to see you try to do this'". In 1976 he was actually taken to court and charged with allowing a woman to do surgery. "I will take the responsibility," he told the judge. "If anything goes wrong, you can put me in jail".

Nothing went wrong. In fact, Zafrullah was winning international recognition for his work.

How Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury had to fight the system to establish his innovative plan

Young women who had completed their secondary school certificate were eligible for training as paramedics. Aged 18–30, they would travel to villages by foot or bicycle, educating people about basic health care and the services available at the hospital, sometimes providing basic treatments or vaccinations.

Every day up to 300 patients visit the Gonoshasthya Kendra outdoor clinic in Savar, about 25 kilometres north-west of the capital Dhaka in central Bangladesh. While government-run hospitals offer low-cost medical care, they are often inaccessible, crowded, understaffed and lacking medicines. Gonoshasthya Kendra serves about 1.2 million people, more than 60% of them poor or very poor.

Holistic approach to disease prevention

Based on his experience of working in the Bangladesh Field Hospital, Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury took on the challenge of developing an effective rural health care delivery system which takes a holistic approach to preventing disease. The emphasis was on the complete wellbeing of a person and not just the absence of disease. He believed that in order to break the cycle of poverty and poor health an effective health care system should be integrated with other social needs such as nutrition, literacy, clean water, good sanitation, family planning and even employment. To facilitate this vision, GK runs several supporting projects, including a university ('Gono Bishwabidyalay' or People's University set up in 1992 to offer courses in Development and Social Sciences, Local Governance and Health Sciences), medical college, vocational training centre, agricultural cooperatives, printing press, community schools and a generic drug-manufacturing plant. But, it is in the health field that its work has been most innovative.

The emphasis on a holistic approach to primary care is particularly significant for a developing nation like Bangladesh which was ravaged by the war. Even now, four decades later, GK still operate on Dr. Zafrullah's founding philosophy and all projects are interwoven with this basic aim.

Concentrating on the poor, GK provided preventative and primary health care services for the surrounding villages where access to health services was almost non-existent. Over the years, GK developed into a complex, integrated rural development project which included other sectors besides health, namely education, nutrition, agriculture, microbiology, vaccine research, herbal medicinal plant research, income generation and vocational training.

The vocational training centre for rural landless women was set up in 1973. The reasons for starting the vocational training centre were related to women's vulnerable position in society which was hindering their access to health services.

Gonoshasthaya Kendra was the first to introduce the concept of paramedics in Bangladesh, an innovation which was later adopted by the Government of Bangladesh in 1977. GK introduced mini-laparotomy method of female sterilisation (tubectomy) in Bangladesh in 1974.

Funding via 'Rural Health Insurance System'

In 1973 GK introduced a 'Rural Health Insurance System' whereby a patient only pays a premium according to their ability to pay and receive essential health care. This means the poor and low income groups are charged lower rates of health insurance premium than the rich and middle class patients who pay much higher rates. However, all groups receive equal quality health care. This ensures GK's services is available for all and is affordable and accessible to the rural masses in Bangladesh.

The introduction of a Rural Healthcare Insurance System in 1973 was probably one of the first of its kind in the world. What started out from a field hospital during war times has evolved into a mammoth social movement involving a university, research establishment, basic drugs and intra-venous fluids producing pharmaceutical setup, printing press for promoting public health.

Currently, GK's breadth and reach has been limited to a small geographic area. However, Dr. Zafrullah believes that with the cooperation of government this can be broadened to national and even international level.

I would say that in the field of paramedical training and domiciliary services, GK has led the way not just in Bangladesh but across the globe.

My intention was to develop a model that can be replicated nationally. Public health is a matter for the state to take charge of. It can never be left to the private sector.

Awards galore

Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury has received national and international acclaim for his integrated community health and family planning services via Gonoshasthaya Kendra.

In 1975 the renowned medical journal Lancet hailed Dr. Zafrullah for coming up with the idea that a grassroots, effective healthcare delivery system can be developed in rural Bangladesh by utilising women as a primary healthcare delivery platform. Two years later, in 1977, he was awarded the Swadhinata Purushkar (The Independence Day Award), Bangladesh's highest national award. This was followed by Magsaysay Award from Philippines (1985), Right Livehood Award from Sweden (1992) and International Health Hero Award from Berkeley University (2002) amongst others. In fact, GK’s innovative programme was accepted as one of the three main background papers for Alma Ata Declaration of the Worlh Health Organization in 1978.

In electing Zafrullah Chowdhury to receive the 1985 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership, the Board of Trustees recognizes his engineering of Bangladesh's new drug policy, eliminating unnecessary pharmaceuticals, and making comprehensive medical care more available to ordinary citizens.

In addition to forming the Gonoshasthaya Kendra, Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury became the founding member of Muktijuddha Sangshad (Freedom Fighters National Council) in 1972 and was elected as its Chairman from 1978-1980. In 1982 he formulated the Bangladesh National Drug Policy which is considered the first comprehensive drug policy in a least-developed country. The Policy ensures "the availability of essential drugs from the grip of predatory capitalist mechanisations of the global pharmaceutical lobby".

It is a crucial matter. If we cannot ensure delivery of even the most basic of drugs then how can you be sure of a public health system.

In 1981 GK set up the celebrated company and factory of Gono Pharmaceuticals (GP) to make essential drugs of the highest quality at low cost. It has been a great success and now supplies an average of 5% of all Bangladesh's drugs, but as much as 60% of some categories. Just as importantly, the fact that its prices were as much as 60% below those of the multinationals has meant that prices generally have fallen greatly. The factory employs some 400 people. Half of its profits are reinvested, half go to GK's social projects.

The GK experience meant that Chowdhury was a key adviser to the Bangladesh government in 1982 when it drew up its Essential Drugs Act, proscribing 1,700 dangerous or useless drugs and setting a unique example to other countries of how to control their market for therapeutic drugs. Detailed plans have now been laid for the establishment of an Institute of Health Science that will train doctors specifically in community health and medicine relevant to Bangladesh's needs.

Dr. Zafrullah also wrote an exhaustive book on the issue, "The Politics of Essential Drugs: The Making of a Successful Health Strategy: Lessons from Bangladesh" which was published in 1995. He also campaigned against commercial food producers from labelling their milk products as substitutes for breast milk.

Be it bringing together freedom fighters, starting the Bangladesh Medical Association in exile or 'raging against the machine' of drugs, healthcare or pointing out how 'research' is used as a new method of colonisation, Zafrullah has been nothing less than a modern-day revolutionary.