Was 3 million Bengalis really killed?

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

There are many aspect of the Muktijuddho which draws up passionate debate regarding the exact detail of event. The Declaration of Bangladesh Independence, the number of Bengali refugees, the role of India, the role of certain Jamaat-e-Islam members are few such examples. However, nothing is as highly sensitive as "the ultimate word-number combination" - the genocide of 3 million Bengalis. It draws strong emotions and in certain Bengali nationalistic circles remains unquestionable.

However, with the death toll for 1971 varying wildly from 26,000 to over 3 million, it's a legitimate question to consider how many people were actually killed and the probability of such high death toll.

It is not uncommon of course for there to be widely different estimates of the numbers who died as a result of a war. People involved in any conflict have reasons to either over or under estimate the numbers who died. Moreover, it is difficult, in any post conflict situation, to make accurate estimates of the numbers of dead, as even recent wars in Iraq, for example, testify.

Extremely sensitive subject matter

Bangladesh is still recovering from the widespread destruction of 1971 Swadhinata Juddho.

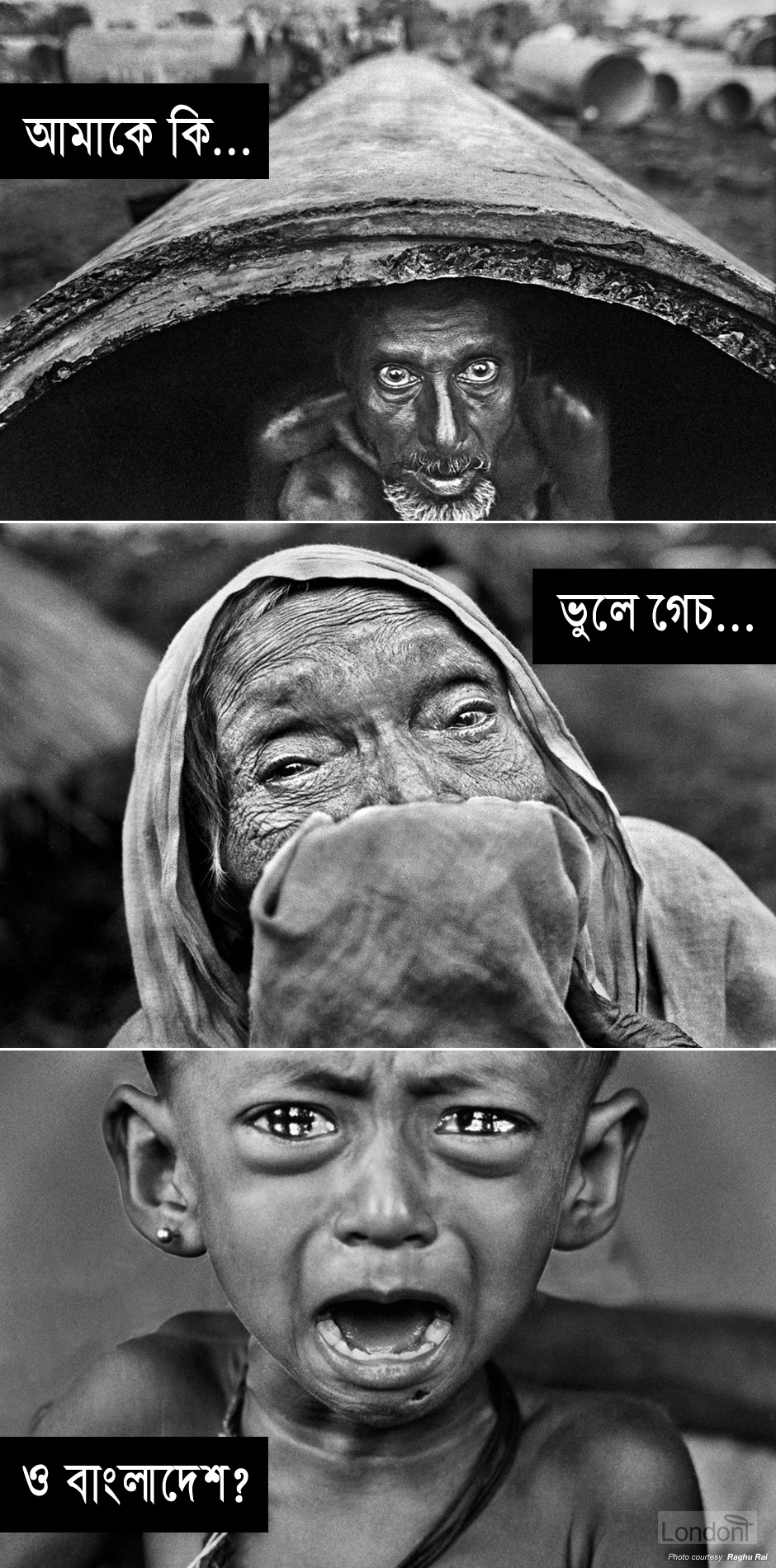

It's been over 40 years and memories are still fresh. Though many people who had undergone that traumatic experience have passed away, there still remain a generation for whom the Muktijuddho topic conjures up unspeakable pain. The word 'Pakistani' triggers intense emotion, usually that of hatred. Influenced largely by the oral history of their elders, this generation prefer to suffer in silence. They've yet to come to terms with what happened. Having first hand experience of those dark days as young adults or children, it is easy to sympathise with them and understand their emotion.

Asked about the traumatic legacy of Bangladesh's 1971 independence — when the territory then known as East Pakistan split from West Pakistan in an orgy of bloodshed — Mojaheed dismissed the need for a proper reckoning with the past. "This is a dead issue," he almost growled. "It cannot be raised".

TIME magazine (2010) interview with Jamaat-e-Islam leader Ali Ahsan Mojaheed prosecuted for alleged war crimes in 1971

An example of the strength of emotion can be gained from the expulsion of Pakistan's Deputy High Commissioner to Bangladesh in 2000. On 30 November 2000 Irfanur Rehman Raja was withdrawn by Pakistan Government after he questioned the number of people killed during 1971 - he put the number around 26,000 (similar to the Hamoodur Commission) and not 3 million -and even refused to apologise for the war crimes committed against the Bengali populace by the Pakistani forces in 1971.

His comments triggered a storm of protest in Dhaka including condemnation and expulsion from different political and civil rights groups and even the Bangladesh government itself. Bangladesh Government lodged a strongly worded protest with the Pakistani Government, forcing it to withdraw him - making Irfanur Rehman Raja the first foreign diplomat to have ever been declared an unwanted person by Bangladesh.

Pakistan says it deeply regrets the decision, saying it was surprising and unjustified and not in keeping with the spirit of friendly relations between the two countries.

Such is the sensitivity around the subject.

Why is the 'number game' important?

Clearly, there continues to exist a considerable amount of debate about the number. Quantifying complex social phenomenon becomes important not only for the Bangladeshi state, but also for the Pakistani state. For Bangladesh the quantification process was critical to indicate the magnanimity of violence during the war and numbers fucntioned symbolically to provide legitimacy for the post-1971 state to emerge as a member of the international community. For Pakistan, it was to question authenticity of Bangladesh's claims of genocide, and demonstrated its distrust. For the victims of the war, the number game produced a constant disempowering rhetoric. As Theodore Porter suggests, quantitative measurements and formal procedures are specific ways to deal with distance and distrust. Numbers, he states offers 'mechanical objectivity and form the basis of knowledge on which strategies are standardised. In the case of the genocide and war crimes in Bangladesh, the politics of numbers also created a social distance between information and the people who generated it.

It's not the arithmetic of genocide that's important. It's that we pay attention.

... Ignorance is an easy thing to live with and, perhaps for that reason, common.

Where did the 3 million figure come from?

The figure of 3 million is believed to have first appeared in the Purbodesh daily newspaper on 23 December 1971, when an editorial stated that 'enemy occupation' had resulted in the deaths of 'about 3 million innocent people'. This figure was then allegedly quoted on the Soviet newspaper, Pravda - the organ of the communist party of the Soviet Union - and subsequently received wider distribution in the Bangladesh media when the news agency ENA picked up the Pravda piece and distributed an article stating that 'The communist party newspaper Pravda has reported that over 30 lakh person (3 million) were killed throughout Bangladesh by the Pakistan occupation forces during the last nine months'.

This [ENA] news agency article was apparently widely covered in Bangladesh newspapers, including for example, the Bangladesh observer, on 5 January 1972.

However, the 3 million figure gained mass appeal when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman uttered it upon his return to Bangladesh on 10 January 1972.

Three million people have been killed. I believe there is no parallel in the history of the world of such a colossal loss of life for the struggle of freedom.

The international media coverage on Bangladesh and on Sheikh Mujib was at its peak during this time. They were very eager to hear from him and to know about his turbulent days behind Pakistani bars. Sheikh Mujib gave several interviews which were covered by globally renowned journalist. During a number of these interviews, including that with prominent British journalist David Frost in January 1972, Sheikh Mujib reiterated that 3 million people were killed.

It was the worst time of my life...when I heard that they have killed about 3 million people my unfortunate [unlucky] people of Bangladesh.

Sheikh Mujib's answer to David Frost's question on his feeling regarding the casualties

These interviews received widespread international coverage which brought the great death toll to people's attention.

Lack of systematic record-keeping

The attempt to collect and compile Muktijuddho history has been fragmented and interrupted. Not enough systematic historical record-keeping of Muktijuddho history has been carried out.

In late January 1972 the newly formed Government of Bangladesh led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman set up a committee, Jatiyo Swadhinatar Itihash Parishad (National History of Liberation War Committee), to look into the number of war dead. The committee was chaired by the Deputy Inspector of Police and collected some records between 1972 and 1973. But the project slowed down and no final report was published - with some suggesting that this was due to the fact that the inquiry had not found anywhere near the number of 3 million deaths.

The project resurfaced again few years later under 'Muktijuddher Itihash Lekhon O Mudron Prokolpo' between 1977 and 1987. The 15 volumes of 'Bangladesher Swadhinata Juddho: Dolil Potro' as edited by Hasan Hafizur Rahman were compiled from this noble task, and remains till date the only official collection of documents on the Liberation War. Reputed historians such as Afsan Chowdhury and Dr. Sukumar Biswas were part of this endeavour. After a 9 year gap, in 1996 another project was undertaken by Mukitjuddho Gobeshona Kendra to collect oral history of the Liberation War. However, after collecting 25,000 interviews in 19 compiled volumes this project was interrupted. Many researchers, including Afsan Chowdhury, have deemed that the historical material available to them are "not adequate" to explain the gradual change in people's political psyche and the transformation in their political will to have an independent Bangladesh.

Not that I was barred from seeing or examining any material I wanted to consult; but I felt, at a phase of my research, that I could see only those documents which the system had permitted to be recorded or preserved over the years. As I found the material inadequate to track the social, political and economic developments leading to the country’s independence, I abandoned the idea of pursuing my PhD on the subject, because I was hungry for total history, and not for a glimpse of it.

Afsan Chowdhury laments lack of depth and empirical evidence on 1971

Matters have been compounded by constant allegation against the two main political parties of Bangladesh, Awami League and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), of trying to 'reconstruct history on party lines' when they come to power and thereby "sharply polarizing society politically, confining history to a description of an iconic event rather than the narrative of the formation of a state" and providing a clouded view of history.

While revising the project documents, we dropped the part on writing the history and increased the volume of documents from six to fifteen. Nobody noticed, nobody complained.

There was no government order stating that all documents relating to 1971 needed to come our way. Rather, it was largely through goodwill and guile that we were able to get our hands on much of these papers. Many of these were simply referring to the activities of activists, partisans and victims, at home and abroad, during the war. Many were technically in the public domain but not accessible, stuck in foreign libraries and offices; but we did receive ample donations of documents, and the fact that we were a fairly reputable lot helped our cause. By 1986, when the project ended, we had brought out 15 volumes of documents, around 1000 pages each, of pure source material, with no comment or analysis.

We worked under a committee made up of very eminent academics, including several of my own teachers, and were neither disturbed nor censored by the government – a fact that was quite unbelievable to many. The documents that we eventually came out with have since become iconic, the foundation of all research on the issue of ‘1971’. However, given a chance to do it all over, I think we could have done a much better job; looking back, some of the errors are glaring. There is no volume on the experience of women, for instance. In addition, some of the interviews and documents on repression – rape, murder, loot and torture – that had been collected before our work began should have been scrutinised more thoroughly, to ensure accuracy. Some were left out as acts of self-censorship, which would have been unacceptable now. In the end, the project work essentially became a narrative of state-making, rather than a description of a social upheaval. The fact of the matter is simply that it never struck any of us that these conceptual issues were involved: we were not dishonest, simply naïve.

It was around this time that I began to think deeply about the idea of sources. Several encounters in particular made me begin doubting the very business of history writing. For instance, I kept hearing about the existence of a host of Foreign Office documents on Indo-Bangla relations, as well as with other major powers. But I kept failing in actually getting my hands on them, despite the efforts of some officials there. My perplexity at this failure was to some extent answered by an officer who eventually told me, straight out, that these documents would simply never be found. "These people gave their opinion in 1971 as rebels," he said. "Now, if those documents are found and are put into print, it will be very embarrassing. It’s not about history; it’s about Foreign Service careers". All of the officers of 1971 are long retired, of course, but the files in question remain 'disappeared'. I remembered the flames that burned for days in the Dhaka Secretariat file-burning oven, as the victorious army approached in December 1971, and could quickly make the connection between history writing, bureaucratic careers and the continuous state.

At another time, we were told by several officers that most of the documents of the Mujibnagar government – the Bangladesh government-in-exile formed by the Awami League – had been sent at one point from Calcutta to the Chittagong port, on a ship named the M V Sandra. But though I made many of enquiries, I was never able to locate anyone who knew of either the ship’s whereabouts or its contents. Many knew about its departure, it seemed, but none knew about its arrival. Eventually, we did manage to cobble together a volume on Mujibnagar, but only because we got lucky. It so happened that the Ministry of Defence of the government in exile had airlifted out all of its documents, which were subsequently kept in a locked room. It was these documents, including office copies of many administrative letters and memos, that ultimately helped us to prepare a full volume on the Mujibnagar government-in-exile.

Initially, the military authorities had promised to hand over the lot of their documents, for which official orders were even passed. But the documents never arrived. Years later, an ex-military intelligence officer admitted to me, over a beer, that he himself had nixed the deal. "You were all fine, but you had a Hindu researcher and he was doing a lot of military history work," he said. "We didn’t trust him, and we never passed the final order".

Perhaps the most insightful experience we had was when we got our hands on a large number of secret files from the Pakistan intelligence service, most from between 1958 and 1962, but some from later years too. These files introduced me to the conspiracies that operate within the management of the state. It was quickly becoming clear to me that there were two parallel narratives with regards to many aspects of the running of the state – and that, the vast majority of the time, the public was privy to only one.

Eventually, the sordid history of Pakistan’s secret service (or, for that matter, any country’s) and its connections with politicians, was to strike me as not nearly as shocking as what I was coming to see as the true nature of my craft. What was a historian to do when he had to deal primarily with documents, even while a great many of the most crucial documents remained purposefully buried from view? Indeed, little more than chance seemed to dictate what could eventually be found and analysed. How could we believe what was being stated when an important source could, potentially, be acting on behalf of another? Looking back on my experience of trying desperately to locate various documents, the whole situation seems now to have been more of an exercise in finding out about how states are formed and run – showing how little we actually knew about these machinations at the time, and perhaps how little we will ever know."

After the formation of the Ministry of Liberation War Affairs in October 2001, the ministry had taken possession of all documents collected by Bangla Academy and Muktijuddho Gobeshona Kendra. A new endeavour started under the ministry to compile the history of sector-wise armed conflict. The original plan of Awami League government in 1996 to collect oral history from all 64 districts and publish a total of 91 volumes of Muktijuddho history was interrupted by the four-party alliance government after the 2001 election.

In the absence of an analytical narrative, it is the emotive content of the war that has been most apparent.

Such interruptions and change of action plan surely creates hindrance in collecting a coherent historical narrative of 1971.

Another curious element of Muktijuddho history I discovered as an MA student researching in the field was the obscurity of Muktijuddho history keeping in Bangladesh. For example, there is no official figure based on empirical evidence of how many people actually died during the nine months of 1971. How many women were raped and how many war babies were adopted by foreign families still remain unknown.

Though a good number of books have been written in Bangladesh around 1971, unfortunately, to the frustration of Western readers, these have been written in Bengali and have not become accessible to non-Bengali readers.

Work are underway to rectify this.

A truth about the Bangladesh war is that remarkably few scholars and historians have given it thorough, independent scrutiny.

We have a lot of 'researches' done and prose, fictions, poetry etc. written on 1971, but most of the works are mere glorification of the middle class valour and heroism displayed in the war. There is hardly any critique or analysis of the political process involved in it.

It is very difficult, indeed, for the writers of middle class origin to go beyond their inherent class-consciousness, especially when the struggle for independence was the construction of the rising middle class of the country. They narrate as ‘history’ what they love to accept as history. Besides, there is the problem of dynastic analysis of history in Bangladesh.

When criticising lack of government initiative remember...

The Government of Bangladesh could have been more proactive in recording muktijuddho history but any criticism to collect statistics needs to consider the magnanimity of the destruction at the time. The country was totally destroyed. Economy collapsed, infrastructure destroyed, international relationship were still being forged and the administrative structure of the new government was still at an embryonic stage.

But, more importantly, the social fabric of the new nation was ruined. Every family had a dark tale to tell. Family member's killed, people missing, women raped, children orphaned, brothers and neighbours once living peacefully became staunch enemies overnight, students forced to become assassins, community leaders killed, and many more gruesome tale.

It was also a nation that was led for the first time by Bengali themselves. The administrative structure was created from scratch and mainly constituted of young, inexperienced politician. Therefore, any commentary on the government methodologies employed during that time to collect war data need to take into account this highly complex and chaotic environment under which the government and its supporters operated. Taking this into consideration, any criticism of the failure of the Bangladesh Government after the war to have undertaken proper studies which would have provided more reliable estimates of the number of dead seem harsh.

That past - Bangladesh's tangled history of violence and discord - goes a long way to explain how one of the 20th century's worst massacres is now largely forgotten in the rest of the world. Bangladesh's origins lie in two bloody partitions: first, in 1947, when British India was carved into two separate independent states, Muslim-majority Pakistan emerged more as a conceit of ideology than one of geography - its two wings separated by a thousand miles of India in between. The artificial union didn't last a quarter-century and Bengali separatism led eventually to a brutal crackdown by the West Pakistani-dominated army, aided by Islamists like Mojaheed and his colleagues, who were loyal to the greater Pakistani cause and who allegedly led or helped organize death squads that targeted Hindus, students and other dissidents. The intervention of Indian troops turned the tide and Bangladesh, as East Pakistan renamed itself, won its freedom in December 1971, its cities hollowed out, the economy in tatters and its population ravaged.

Clarity on victim's role

One critical point that needs clarification whilst determining the number of dead is who forms part of that number?

Amongst the dead how many of these were:

- Muktijuddhas who were killed in combat?

- Bihari Muslims and supporters of Pakistan killed by Bengalis?

- killed during cross-fire between Pakistanis, Indians or Mukti Bahinis?

- death resulting from war but not necessary the result of fighting and atrocities such as disease (especially cholera) and malnutrition?

One thing is clear - the atrocities did not just go one way, though Bengali Muslims and Hindus were certainly the main victims.