International photographers

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

Photography is a universal language. Like their Bengali counterpart, many young and upcoming international photographers captured the untold agonies of the innocent Bengali people through their lens.

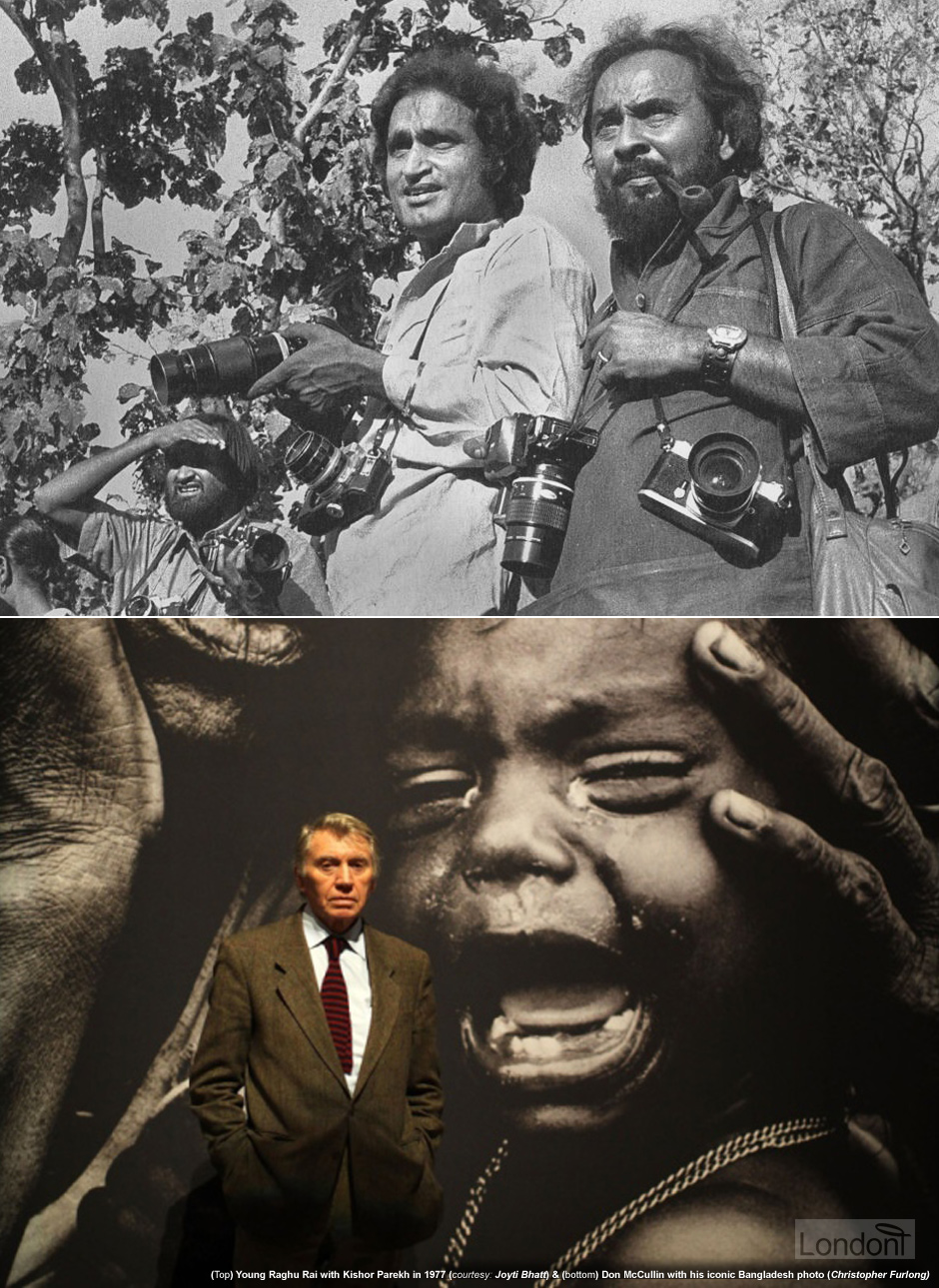

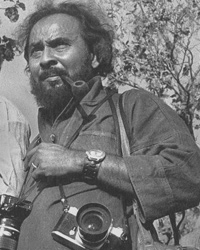

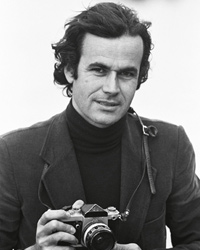

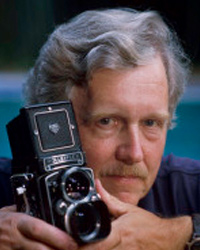

On foreign soil thousands of miles away from home, these brave souls were determined to inform the wider world of the Pakistani genocide by venturing into unknown territory. These photojournalists, who later became internationally acclaimed photographers, included Indian Raghu Rai, Kishor Parekh and Bal Krishnan, Abbas (Iranian), Don McCullin and Marilyn Silverstone (English), Michel Laurent, Raymond Depardon, Marc Riboud and Bruno Barbey (French), Horst Faas and Otto Bettmann (German), Mary Ellen Mark, David Burnett and Mark Godfrey (American), amongst others.

Raghu Rai ()

Raghu Rai ()  Abbas (Attar) ()

Abbas (Attar) ()  Kishor Parekh ()

Kishor Parekh ()  Don McCullin ()

Don McCullin ()  Michel Laurent ()

Michel Laurent ()  Horst Faas ()

Horst Faas ()  BegArt Institute of Photography ()

BegArt Institute of Photography ()  Raymond Depardon ()

Raymond Depardon ()  Bal Krishnan ()

Bal Krishnan ()  Marylin Silverstone ()

Marylin Silverstone ()  Christian Simonpietri ()

Christian Simonpietri ()  Marc Riboud ()

Marc Riboud ()  Otto Bettmann ()

Otto Bettmann ()  Bruno Barbey ()

Bruno Barbey ()  David Burnett ()

David Burnett ()  Mark Godfrey ()

Mark Godfrey ()  Mary Ellen Mark ()

Mary Ellen Mark ()

I had a very baby-like face when I began. I think these people used to look at me and think, 'What’s this kid doing behind a camera in the middle of a war zone?' So they would look up at me in curiosity.

You cannot be objective. Sometimes people criticise my work as a journalist because it's so interrelational, and therefore very self-consciously subjective. What people don’t always understand is that, when you go there, it is with the chance of being killed as well. I gambled my life for the photographs I took on those days.

You press that 'professional' button, you think: 'Is this the best composition, the best expression, the best action shot?' But then you remember that you are also a human being standing in front of another human being; you’re not just some robot here doing this.

...I’ve had hundreds of starving children staring up at me, thinking I was their salvation. It has not been an easy cross to bare. We're all guilty. We’re guilty by association. Of course I’m guilty. I feel ashamed standing in front of people with a camera and knowing that I could leave anytime and get myself something to eat. When I was working on some of those AIDs stories, I would never sit and eat in front of them. I would go and hide in a warehouse or somewhere. I know what shame is and that I can be easily part of it. When I photographed the picture of the baby burnt to death, I was full of shame. Not only for myself, but also for the people that did it, the whole thing was despicable; I constantly watch how I behave, checking my moral obligations.

Rai first went in August to document the stories of refugees, and then again in December, with the Indian army. Those two journeys are distinct—one tells the story of a human tragedy; the other of human conquest, culminating in the Pakistani army’s surrender to Indian forces and Bangladesh’s founding father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s triumphant return in 1972.

...Rai first went to witness the story of refugees from East Pakistan in August 1971. As he notes, in August "the monsoon was at its peak. The skies were deep grey and it was raining all the way. The border was not just porous, it was overflowing from all sides. The refugees with their meager belongings were pouring in ... they were drenched by the rain, suffering and fatigued. There was a kind of a silence - nobody was talking. There was nothing the others did not know". Their lives were now lived in public; they were part of a human drama the world was meant to witness. Rai was among those who made sure it did.

What the refugees didn’t speak about was how their crops were burned (Rai shows us scorched land), their homes razed (we see shells of homes), their women raped (in a moving photograph, Rai closes in on a young woman lying on a cot, wearing a sari without a blouse, her eyes still and dry, her belly bigger than her slender frame, indicating the child she is carrying but did not want, personifying the harrowing saga of rapes during that war; by some estimates, there were more than a quarter million rapes). And even though you only see her in the photograph, you get her sense of loneliness - she is possibly shunned because the father of that child she is carrying is a Pakistani soldier. The relentless violence and humiliation the farmers and fisherfolk and boatmen faced are visible in the exhausted faces of the refugees, their wrinkles pronounced, their tears glistening.

The photographs are in black and white. Rai goes close enough to a man’s face to let you count the whiskers on his face. His camera stops near the bloodstains on a sari. The head looks up in another image, and you want to caress the wounded brow. He sharpens the focus on the human being at the centre of the image, separating him from the detritus of what remains of the possessions that he carried with him across the border. The queue of refugees shows some who are wizened, some determined, carrying their children on their shoulders, their possessions on their heads. A little boy walks, wearing only a buttonless shirt, smiling and talking to older boys, oblivious to his surroundings. They are leaving their past, walking to a different future.

'Future' and 'safety' lie across the river, to cross which the boatman may demand the last bag of rice the refugee is carrying. Times are bad, but business is business. There are ten million of them, overwhelming the Indian state—for some time, Tripura has more refugees than residents. They live in large pipes and in makeshift tents. Rai shows a stack of pipes, their interiors dark, except for the men who raise their heads and stare back at this odd man taking their photographs. They live on rations, forming orderly queues which go out of focus as Rai fixes the lens on the few in the front of the queue. Children are bathed, old people die, rain lashes the landscape, diseases spread easily and are fought by stubborn nurses and doctors working selflessly, round-the-clock, in the camps.

The lives of these "millions" are lived in the open: nothing is confidential, nothing secret. Rai witnesses it, clicks the image, preserves it, recording it for posterity.

I saw the sufferings of thousands of refugees, who were coming to India. I did not know Bangla, but the pain I saw in their eyes said more than a thousand words that I captured in my photos. And I believe, anybody from any corner of the world still can feel the pain and gravity of the brutality inflicted on them.

I saw the cry of the hungry children, the pain of the mothers and wives who lost their sons and husbands, the anxiety of the people who left their homes and many other things. But the most striking was to see the impassive faces of the raped women who had nothing else left to lose.

I was wondered by seeing the activities of Muktibahini who, with no professional training and a very small quantity of outdated weapons, fought against Pakistani Army. It was their firm determination which made them defeat the Pakistani regimented force.

I shared the proud moments with Bangladeshi people when they finally achieved the freedom. It was great to be the part of the journey of the birth of a nation.

For a photographer, what sets apart a war zone from other locations is the imminence of danger. Raghu Rai had gone along with the first column of Indian troops entering what was still officially East Pakistan from the Khulna border in early December 1971. Pakistani forces had retreated to defend the capital, Dacca, as it was then known. But after they had travelled about 50 km, Pakistanis attacked with artillery fire. Rai shot photographs of wounded soldiers being taken away. After the situation subsided, Rai was relieved to find a teashop and decided to have a moment’s respite, although the Indian army major told him to be careful. Just as Rai ordered tea and biscuits, a bullet whizzed past him. "The major shouted for me to lie down," Rai wrote. "I did, and another bullet went past me. I crawled back to the shop and was told by the shopkeeper that the Pakistani army was on the other side of the railtrack, just half a kilometer away".

Photographers are meant to be impartial observers, or witnesses. But to the Pakistani sniper, Rai was a participant, entering enemy territory, accompanied by a foreign army. He was a target, fair game. He may have come to record, but he was intervening.

[Raghu] Rai's images have served another purpose, though. At the time, he says, Pakistan’s propaganda on the world stage was stronger than India's. Even Prime Minister Indira Gandhi did not believe the scale of migration till she travelled to the border areas and saw it for herself. Rai decided to exhibit his refugee series in Europe - in Prague and Paris, among other cities. "That’s when the Indian Government realised the power of photography", he says. It got him a Padma Shri award in 1972.

[Kishor] Parekh, who is credited with changing the face of Indian photojournalism during his years at The Hindustan Times starting in the 1960s, was working in Hong Kong when the 1971 war broke out. For someone who had earlier covered the Sino-Indian war of 1962, the conflict with Pakistan in 1965 and the Bihar famine of 1966-67, it was troubling, his son Swapan Parekh remembers his mother recounting, to be "sitting on a beach and painting while his country was burning".

Unwilling to sit it out, and undaunted by his boss' apathy towards a war raging far away, Parekh took off on his own, hitching a ride to the border, where he found a helicopter waiting to take accredited mediapersons across. Parekh did not qualify. Swapan, a photographer himself who has pieced together this story from accounts of his mother and father's friends and colleagues, says his father simply barged his way in. "Take me or shoot me", he told an Army major who was trying to stop him. He was taken on the condition that he would be on his own across the border.

Once in East Pakistan, he hitched rides on trucks, and on one occasion even got nabbed by the Indian Army on suspicion of being a Pakistani spy. Thanks to Parekh's charm, this episode ended with the Army handing him a major's uniform and inviting him to travel with them. It was during this time with the forces that Parekh and Rai were likely to have been together for a few days, leaving us a record of the same scenes seen through two different pairs of eyes.

Both a fighter and a photographer

The majority of the participants in the Bangladesh Liberation War were young Bengali peasants and students. Amongst them was young Haroon Habib who was studying Journalism at Dhaka University. After the war broke out, Haroon travelled to Indian state of Meghalaya with a group of 150 fellow Bengalis to train for combat.

If we look back at 1971, we'd see a war which was won by the ordinary people. Villagers, students and civilians with no military background, took up arms without a second thought.

Haroon was recruited by the Mujibnagar Government as a war correspondent and worked for Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra and 'Joi Bangla', a newspaper published by the Mujibnagar Government.

When the Bangladesh Forces were organised into eleven sectors, Haroon went to Sector 11. This is when the Sector Commander Major Abu Taher gave him a Yashica camera. This camera captured most of the images we see with him today (his first camera belonged to Dr. Humayun Hai). Buying film was difficult and printing it was an even bigger task: one had to travel 60 km inside the Indian border to get to a printing studio. Haroon printed most of his pictures at a studio in the Tuha Hills of Meghalaya.

During subsequent months Haroon took a total of 100 rare photographs covering freedom fighters in training and combat, meeting between Pakistani soldiers and 'Shanti Committee', refugee camps (with one rare one showing Indira Gandhi visiting a camp in Tripura), joint Indo-Bangladesh operation, and ordinary lives of people including people taking part in the Eid prayers in 1971, amongst other. Two of the children that he had photographed grew up to be medical doctors.

It is only in recent years that Haroon’s photographs were made public at various exhibitions such as "Muktijoddhar Camera-e Muktijuddho 1971" jointly organised by Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy and Ekattur-er Jatri at the National Art Gallery on 25 March 2010. Since then, many have also found place as permanent exhibits on his walls. Each photo is neatly captioned, dated (when the date is known) and now, also digitised. Haroon hopes that his photographs would contribute in bringing awareness to the people regarding the true history of the war and also educate the post-war generations.

When young children from the neighbourhood drop in to look at the pictures and hear the stories he has to share, Haroon is happy that the photographs can serve as living pieces of history for current and future generations.

Haroon Habib was not alone in fulfilling the dual role of a guerrilla and a war correspondent. Freedom fighter Lokman Hossain from Manikganj district also did the same. Lokman Hossain, known locally as 'Tiger' Lokman, was in the Pakistan Army at Chittagong Cantonment in 1966. However, after the war broke out he joined other fellow muktijuddhas at the end of April 1971 and led a fierce battle against the Pakistani occupation army at Golaidanga village in Singair upazila on 28 October 1971 - killing at least 83 Pakistani soldiers.

I went to Captain Abdul Halim Chowdhury at Sutalari village under Harirampur upazila in the district, he sent me to Singair with two others. As per his order, we went to the house of Salam, brother of language martyr Rafique Uddin Ahmed, at Paril village, by a boat in the month of June. We joined Engineer Tobarak Hossain Ludu there. Then we recruited 35 young men from the village and neighbouring areas.

We took position at Golaidanga around 7.00 am on 28 October 1971 as Kismot Munshi of Paril village informed us that the Pak soldiers were coming by seven boats. As soon as they came close, we fired on them and 83 Pak soldiers drowned in the river. We later recovered 54 arms including LMG, Chinese rifle, mortar shell etc. from the spot. Zahidur Rahman, Pannu, Yakub, Tobarak Hossain Ludu, Wazed, Lutfar, Mahadev, Bhabesh, Maznu, Zahangir, Ginu and a few other freedom fighters were with me. In the evening, the occupation forces come to the spot with helicopter. They recovered the bodies and took them to Dhaka

Nevertheless, despite the unimaginable difficulties that he endured, Lokman kept clicking pictures wherever he was. Armed with his simple camera, Lokman Hossain captured many rare images of fellow fighters and events that he encountered. Post-independence Lokman has set up a gallery at his home in Ashapur village, Ghior upazila (Manikganj district) to preserve and display the photographs commemorating the glorious role of his fellow freedom fighters and himself during the turbulent days of the Liberation.

Haroon Habib ()

Haroon Habib ()  Lokman Hossain ()

Lokman Hossain ()

Others, had recorded 1971 in their own way. Taking great risks as amateurs, preserving a history of our birth pangs, knowing it could signal death.