Why didn't India intervene earlier?

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

Post 1947 independence, India had fought three military conflicts - two with Pakistan (First Kashmir War 1947-1948 and Second Kashmir War 1965, more popularly known as Indo-Pak War of 1965) and one with China (Sino-Indian Border Conflict 1962). Therefore, an East Pakistani-dominated central cabinet, it was assumed, would be less inclined to raise the issue of Kashmir (than the previous governments of Pakistan) which has been at the heart of India's two major war with its neighbour.

All eyes were now focused on Indira Gandhi, known for her decisive, resolute and timely actions.

Pro-attack campaigners: "Opportune moment to break-up Pakistan"

Domestic pressure notwithstanding, the initial Indian reaction was relatively cautious. Indian paramilitary Border Security Force (BSF) troops began providing low-level assistance to Bengali freedom fighters in early April in the form of safe havens, training, and limited arms, but New Delhi chose not to officially recognise the Provisional Government of Bangladesh (declared on 17 April 1971) and it did not authorise direct military action across the border.

Those in favour of intervention argued that helping East Pakistan to secede from Pakistan would improve India's security as East Pakistan was "captive" to India and thus weaken Pakistan's stance. They'd also have the second largest Muslim population in the subcontinent after India.

Some retired generals publicly argued in favour of immediate military action before Pakistani forces could be strengthened by the arrival of heavier weapons and ammunitions by sea. The more time India allowed Pakistan, they argued, the more costly would the venture become militarily. It was time to act now, they echoed.

However, India had its own problem. And Manekshaw had his own justifiable reservations about instant action

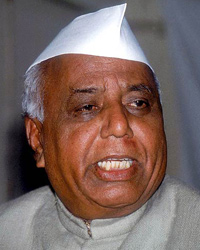

(Babu) Jagjivan Ram (1908 - 1986) Deputy Prime Minister of India (1977-79) and Minister of Defence (1970-74). Known popularly as 'Babuji'.

(Babu) Jagjivan Ram (1908 - 1986) Deputy Prime Minister of India (1977-79) and Minister of Defence (1970-74). Known popularly as 'Babuji'. Yashwantrao Balwantrao (Y. B.) Chavan (1913 - 1984) First Chief Minister of Maharashtra and fifth Deputy Prime Minister of India.

Yashwantrao Balwantrao (Y. B.) Chavan (1913 - 1984) First Chief Minister of Maharashtra and fifth Deputy Prime Minister of India.

West Bengal problem

In the preceding winter parliamentary elections brought a win for the ruling Congress Party after it had split into different faction in November 1969. Indira Gandhi won a dazzling victory in March 1971, winning more than two-thirds majority in Lok Sabha, and this spurred her to establish a stable government in anarchy-ridden West Bengal. From the collapse of the coalition government in March 1970 and the imposition of presidential rule, some political murders were reported to have been committed in clashes between the Maoist Naxalites led by Charu Mazumdar and other political groups. It was feared that the communist element within East Pakistan my merge with this West Bengal Naxalite organisation and create havoc for the Indian government. As such intensive anti-terrorist campaign was being waged in West Bengal by India's Central Reserve Police and army - the official policy was to prevent linkages between the insurgencies by West Bengali and East Pakistani "extremist". In light of these developments, some of the prominent Indian ministers advised the government against any sort of military or political involvement in East Pakistan in order to avoid 'creating conditions that would encourage autonomy movements in its own territory'.

Bangladesh, they noted, meant "country of the Bengalis", and India had a large number of Bengalis in its population who may be attracted by the "Amra Bengali" (We're Bengalis) concept of a unified, independent Bengal.

Chinese threat

Pakistan had developed a close alliance with China, which was greatly strengthened after the Indo-China war of 1962 when China dealt a brutal and humiliating defeat to the Indian Army over, amongst other things, disputed territory along the 3,225-kilometer-long Himalayan border shared by the two nations. The United States, too, was an important ally in the Cold War - a sustained state of political and military tension between US-led West and Soviet-led East from 1945-1991 - as it was able to depend on the Pakistani military to fight communism.

Pakistan's strong relationship with China can be gathered from the well-set routine of its leaders to make frequent visits to China. Among Bhutto's first trips after taking over as President were his trip to China and the Muslim Middle East. While in power, Bhutto visited China three times - in 1972, 1974 and 1976. Prime Ministers Benazir Bhutto - Zulfikar's eldest daughter - and Nawaz Sharif continued with this policy. General Musharraf was a frequent visitor to China and President Zardari had undertaken four trips to China within one year of taking office in September 2008.

China blocked the admission of Bangladesh to the United Nations from August 1972 till 1974, after Bangladesh was given official recognition by Pakistan during the OIC Summit held in Islamabad, Pakistan. The Chinese government also wrote off four loans amounting to $110 million and deferred for 20 years the repayment of the 1970 loan. Between 1956 and 1979 Pakistan received $620 million in economic aid from China, about one-third of China's total aid to Asia and the Middle East.

China gave military aid to Pakistan from 1966 until the outbreak of the East Pakistan crisis in 1971, serving as Pakistan’s main source of arms - Beijing contributed over $130 million worth of military equipment and supplies during the five year period from 1961-1966. China supported Pakistan politically, morally, and materialistically, even after the US discontinued military shipments in March 1971. On 12 April 1971, Chinese Prime Minister Chou En-lai promised all help to Yahya Khan in maintaining the "territorial integrity of Pakistan" against all "external interference", which included the "handful of people" waging guerrilla war in Bangladesh.

The main points of Chou En-Lai message to to Yahya Khan were:

- the "happenings in Pakistan" is "a purely internal affair" to be solved by Pakistani people without "foreign interference". This favored the principle of non-intervention could also be seen in China’s protest Note to India of 6 April 1971;

- that China opposed the separatists as was seen in the expression: "The unification of Pakistan and the unity of the people of East and West Pakistan are the basic guarantees" for Pakistan’s prosperity and strength;

- China felt the separatists to be in a minority, "a handful of persons who want to sabotage the unification of Pakistan";

- on the issue of solving problems, China's preference for negotiations can be see in the expression that "through the wise consultation and efforts" of the Government and "leaders of various quarter in Pakistan", the situation will remain peaceful;

- taking note of the "gross interference" by India in the affairs of Pakistan, China understood the US and the USSR collusion with India. In the protests note of 6 April also China accused India of "'flagrantly' interfering in the internal affairs of Pakistan";

- that China's support to Pakistan was assured if "the Indian expansionists dare to launch aggression against Pakistan".

On 30 April 1971, Bhutto, the most ardent pro-Chinese politician in Pakistan, declared China would intervene in the event of an Indo-Pak conflict over Bangladesh. This statement was soon followed in May by the Pakistani Ambassador in Peking, who, at a reception to mark the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Pakistan, hailed the ready Chinese "unflinching and forthright" support in Pakistan's difficulties with India.

Nevertheless, the Chinese did not openly clarify whether their 'support' would be in military terms, as the Pakistanis preached throughout 1971, or only on diplomatic support abroad and economic aid at home and supply of arms. The Chinese made it clear that their intervention was conditional on "foreign aggression" against Pakistan and India had no intention of starting the war with Pakistan first.

With the threat of the Chinese looming, the ideal time for hostilities from the Indian point of view would be December. The Himalayan passes would then close for about five months. It would reduce the potentiality of Chine collusion and would enable India to take greater risks against the Chinese by thinning out its holding force in the Himalays to create the required buildup of troops against Pakistan, particularly in the eastern theatre. It would also enable India to tilt international opinion in favour of Bangladesh, with a view to seeking help in meeting the crushing economic burden of looking after millions of refugees as well as a political solution with Yahya Khan which would create stability in the subcontinent.

Sam Manekshaw: "Indian Army not ready, yet"

On 29 April 1971 Indira Gandhi held a meeting in which she apparently considered ordering a military advance. However, Foreign Minister Swaran Singh counseled restraint and recommended holding military intervention until "interim measures did not resolve the East Pakistan crisis" diplomatically.

His views were shared by Sam Manekshaw. He advised Indira Gandhi that India's armed forces would need many months to prepare for conflict. Though militarily the pre-monsoon period (April to mid-June 1971) was perhaps the most favourable to both countries, India was not ready strategically or resource-wise. In addition, the imminent arrival of the monsoon would prevent major operations until November at the earliest.

Firstly, Manekshaw argued, due to previous Indo-Pak conflict in the western wing, the contingency planning in the east was not fully catered for. There was limited resources dedicated on that side, and also the eastern region of Tripura (next to Bangladesh) lacked the necessary administrative and communication infrastructure to support worthwhile operations. Secondly, the large force required in such a conflict would need time to collect. Many of the troops were engaged in counter-insurgency and other holding roles in far-flung areas, and some were tied up in the potentially explosive West Bengal elections. By the time the force was collected the monsoon would be on its way, thus leaving a very tight schedule for the operation. Finally, there was a shortage in stockpiled reserves of essential specialised and armoured vehicles and of bridging equipment which would need some time to make up and recoup. In addition, raising new units and formations and the introduction of newly acquired equipment was in progress, and this needed time to assimilate. Even with crash programming, these tasks, could not be completed before the onset of the monsoon, and then it would be too late.

Recalling his Burma campaign days, Manekshaw did not want his army to get stuck in the quagmire of the monsoon. Moreover, this would give China, a sympathiser of Pakistan and a foe of India, a chance to retaliate on India's northern borders. China would have about eight months of campaigning, till the Himalayan passes closed sometime in November, to annexe the maximum Indian territory. Manekshaw preferred to fight one enemy at a time, and the weaker one first. He proposed to time his military action for November, when the possibility of Chinese participation was considerably reduced because the Himalayan passes would then be closed.

The Indian Army, Manekshaw concluded, was not ready to reorient operational plans rapidly at such short notice. Beyond the military aspect of intervention, there was the political compulsion which clinched the issue.

Swaran Singh ()

Swaran Singh ()  Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw (1914 - 2008) Field Marshall of the Indian Army. Also known as "Sam Bahadur" (Sam the Brave)

Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw (1914 - 2008) Field Marshall of the Indian Army. Also known as "Sam Bahadur" (Sam the Brave)

Justifying intervention

Questions were also raised about the Awami League's capability to control policy making in the face of strong pressure from the military and some West Pakistani parties. Then there was the sensitive issue of redistribution of Ganges River waters, where Awami League were more hardline than their West Pakistani colleagues since East Pakistan was the area most seriously affected.

Other Indian ministers were also concerned with international reaction, especially from several Islamic states with whom India had important ties.

What was the invasion of East Pakistan based on, what internal problem did it have which could be justified in international circles? If the creation of an independent Bangladesh was achieved by Indian military action, how was its domestic and external viability to be assured without its recognition by the international forum, the United Nations? If India intervened without clearly justifying the action in foreign eyes, the charge that it was engineering the breakup of Pakistan would be established and Bangladesh would be refused recognition by the majority of nations.

Thus, while East Pakistan was the most widely and intensely debated issue in India throughout 1971, the total effect of all this clamor on decision making was negligible. From 25 March to end of May, New Delhi discouraged projections of a major Indian role in the resolution of the crisis in East Pakistan, which did not make good political or strategic sense. The Indian army was prepared neither for direct intervention in East Pakistan nor for the inevitable counterthrust from West Pakistan. New Delhi considered it essential to assist in the creation of a resistance movement in East Pakistan as the political and military basis for direct Indian intervention. If military action were unavoidable, India preferred that its moves be interpreted as supportive of a Muslim-led East Pakistani liberation movement rather than just another Indian-Pakistani (i.e. Hindu-Muslim) conflict.

For the Indian government it was a question of timing and the political sensitivity of the crisis. Wary of intervening in the Pakistan issue in the spring of 1971 - which would have been condemned by most of the international community, including some of India's friends - in the first stage of the crisis, Indian government placed great emphasis on the duty of the international community to bring pressure on Pakistan for a political solution that met the East Pakistani demands. For example, establishing the popular Awami League government and the safe return of all refugees.

We have sought to awaken the conscience of the world through our representations to the United Nations, and, at long last, the true dimensions of the problem seem to be making themselves felt in the sensitive chanceries of the world. However, I must share with the House our disappointment at the unconscionably long time which the world is taking to react to this stark tragedy...

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi told her Parliament on 24 May 1971

After considering the issue carefully, Indira Gandhi accepted the postponement of intervention to an opportune moment in the future and supported Manekshaw in his stand. She agreed to a delay, but ordered Manekshaw to plan for war as a policy option for the future. Meanwhile, the Indian Government gave the international community an opportunity to act whilst they felt they were not in a position to do much themselves.