"Ebarer sangram amader muktir sangram - ebarer sangram swadhinatar sangram"

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

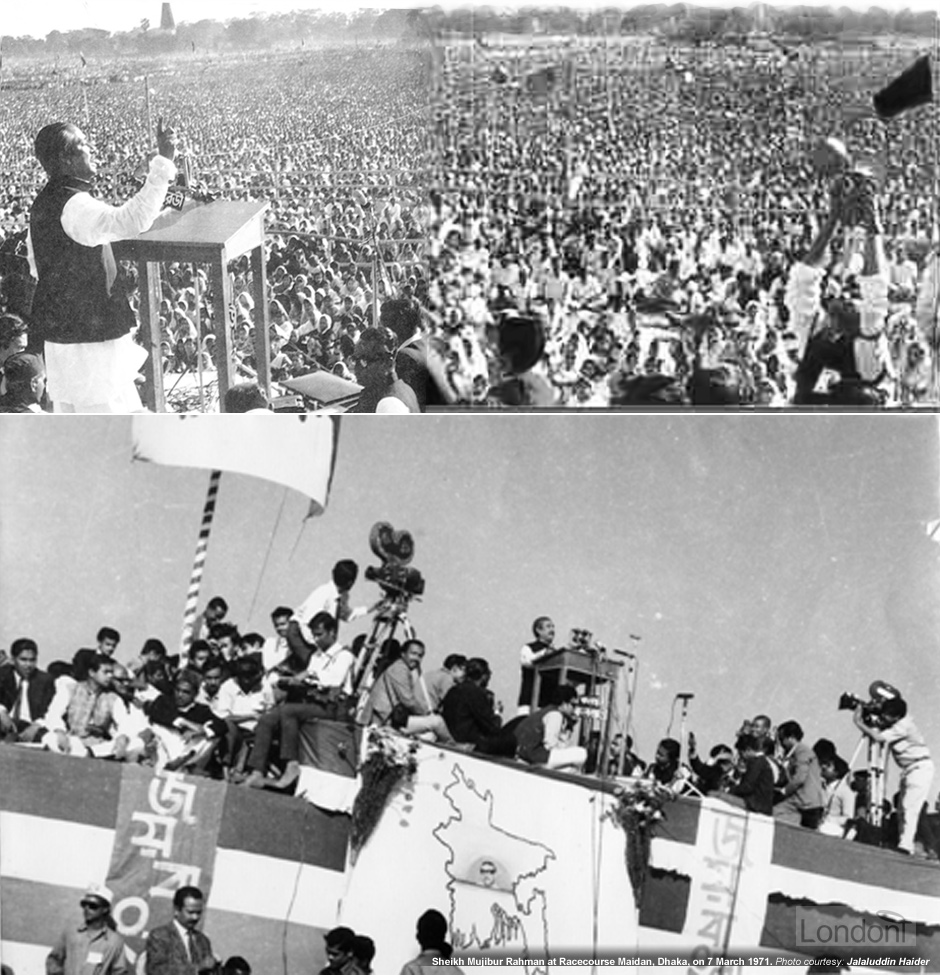

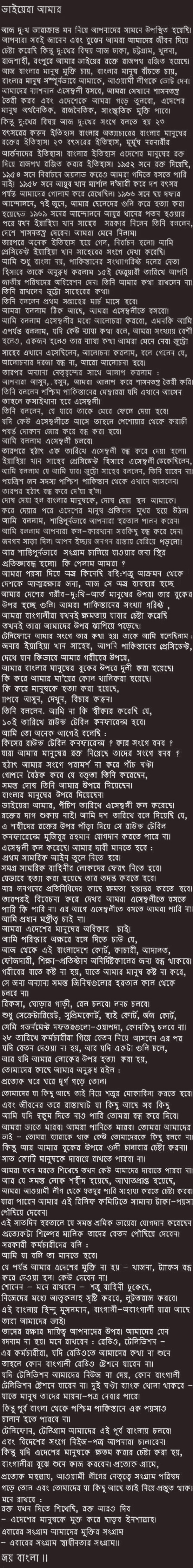

On the last day of the hartal, 7 March 1971, Awami League called a mammoth public gathering at Dhaka's historic Race Course Maidan (or Race Course Ground, the then name for Suhrawardy Udyan) to respond to the boiling tension across the province. Around 1 million Bengalis - the Bangladesh Ministry of Cultural Affairs puts this number around 2 million - gathered in anticipation of their leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Party hardliners demand unilateral declaration of independence (UDI)

On that historic day the student leadership of what was now called the 'Bangladesh Chhatro League' (no longer East Pakistan Chhatro League) presented Sheikh Mujib with an ultimatum: he must declare independence or they would abandon him and take an independent course.

Since the strings of the movement were in our hands, Mujib did not dare to defy us.

Harunur Rashid, a student activist during 1971 and later the Acting General Secretary of the JSD

Is the West Pakistani Government not aware that I am the only one able to save East Pakistan from communism? If they take a position to fight I shall be pushed out of power, and the Naxalites will intervene in my name. If I make too many concessions, I shall lose my authority. I am in a difficult situation.

There was very high risk in such a bold stance. General Tikka Khan and his army stood ready to pounce on Sheikh Mujib and the Bengali people if there was an open, unilateral (one-sided) declaration of independence (UDI). However, Sheikh Mujib would prove a whole lot smarter than the regime, and even his close associates who demanded that he declare Bangladesh's independence.

The time was not right for an open declaration, Sheikh Mujib thought. There were over one million innocent, unarmed civilians in the audience who were circled by west Pakistani helicopters in the sky like vulchers ready to annihilate them. An UDI at this moment would prove suicidal. It would also turn the Bengali's struggle for freedom into a 'separationist' movement and thus alienate international support. Instead, Sheikh Mujib left no doubt in the public mind and to the Pakistani military junta (committee) that he was leading his people down freedom road.

You go ahead with your preparations for the independence war while I am playing a wait-and-see game with the Pakistani leaders.

There were many who expected Bangabandhu to go for a unilateral declaration of independence for Bangladesh. There were others who waited to see what his political wisdom, garnered over years of experience, would bring forth for the seventy five million people of what was yet a province of the state of Pakistan. In the event, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman demonstrated his mettle in no uncertain terms. He would not go for UDI, for that would leave him open to charges of political adventurism. And he would not, under any circumstances, give Pakistan’s ruling classes any reason to think that he was about to come round to their expectations of a compromise he would agree to. Most significantly, he would let his people know that sovereignty was the goal, but it would be sovereignty arrived at on strong constitutional foundations. If constitutionalism did not work, the nation would find other, necessarily radical means to wage its war for freedom.

Syed Badrul Ahsan, Journalist

Sheikh Mujib and THAT speech

In an 11-minute long speech by Sheikh Mujib the future of Pakistan would be decided. This historic address would prove to be the final nail in the coffin for an united Pakistan and would provide the green light for the Bengalis to finally fight for their freedom and look forward for redemption for their sufferings and deprivation of the preceding 23 years under West Pakistani rulers. It seemed as if Bangladesh had in fact come into existence.

The time was about 2.35 pm.

In Bangla

In English

Brother of mine,

I have come before you today with a heavy heart.

All of you know how hard we have tried. But it is a matter of sadness that the streets of Dhaka, Chittagong, Khulna, Rangpur and Rajshahi are today being spattered with the blood of my brothers, and the cry we hear from the Bengali people is a cry for freedom, a cry for survival, a cry for our rights.

You are the ones who brought about an Awami League victory so you could see a constitutional government restored. The hope was that the elected representatives of the people, sitting in the National Assembly, would formulate a constitution that would assure that people of their economic, political and cultural emancipation.

But now, with great sadness in my heart, I look back on the past 23 years of our history and see nothing but a history of shedding the blood of the Bengali people. Ours has been a history of continual lamentation, repeated bloodshed and innocent tears.

We gave blood in 1952, we won a mandate in 1954. But we were still not allowed to take up the reins of this country. In 1958, Ayub Khan clamped Martial Law on our people and enslaved us for the next 10 years. In 1966, during the Six-Point Movement of the masses, many were the young men and women whose lives were stilled by government bullets.

After the downfall of Ayub, Mr. Yahya Khan took over with the promise that he would restore constitutional rule, that he would restore democracy and return power to the people.

We agreed. But you all know of the events that took place after that I ask you, are we the ones to blame?

As you know, I have been in contract with President Yahya Khan. As leader of the majority party in the National Assembly, I asked him to set February 15 as the day for its opening session. He did not accede to the request I made as leader of the majority party. Instead, he went along with the delay requested by the minority leader Mr Bhutto and announced that the Assembly would be convened on the 3rd of March.

We accepted that, and agreed to join the deliberations. I even went to the extent of saying that we, despite our majority, would still listen to any sound ideas from the minority, even if it were a lone voice. I committed myself to support anything that would bolster the restoration of a constitutional government.

When Mr Bhutto came to Dhaka, we met. We talked. He left, saying that the doors to negotiation were still open. Moulana Noorani and Moulana Mufti were among those West Pakistan parliamentarians who visited Dhaka and talked with me about an agreement on a constitutional framework.

I made it clear that could not agree to any deviation from the Six Points. That right rested with the people. Come, I said, let us sit down and resolve matters.

But Bhutto’s retort was that he would not allow himself to become hostage on two fronts. He predicted that if any West Pakistani members of Parliament were to come to Dhaka, the Assembly would be turned into a slaughterhouse. He added that if anyone were to participate in such a session, a countrywide agitation would be launched from Peshawar to Karachi and that every business would be shut down in protest.

I assured him that the Assembly would be convened and despite the dire threats, West Pakistani leaders did come down to Dhaka.

But suddenly, on March 1, the session was cancelled.

There was an immediate outcry against this move by the people. I called for a hartal as a peaceful form of protest and the masses redial took to the streets in response.

And what did we get as a response?

He turned his guns on my helpless people, a people with no arms to defend themselves. These were the same arms that had been purchased with our own money to protect us from external enemies. But it is my own people who are being fired upon today.

In the past, too, each time we, the numerically larger segment of Pakistan’s population-tried to assert our rights and control our destiny, they conspired against us and pounced upon us.

I have asked them this before: How can you make your own brothers the target of your bullets?

Now Yahya Khan says that I had agreed to a Round Table Conference on the 10th. Let me point out that is not true.

I had said, Mr Yahya Khan, you are the President of this country. Come to Dhaka, come and see how our poor Bengali people have been mown down by your bullets, how the laps of our mothers and sisters have been robbed and left empty and bereft, how my helpless people have been slaughtered. Come, I said, come and see for yourself and then be the judge and decide. That is what I told him.

Earlier, I had told him there would be no Round Table Conference. What Round Table Conference, whose Round Table Conference? You expect me to sit at a Round Table Conference with the very same people who have emptied the laps of my mothers and my sisters?

On the 3rd, at the Paltan, I called for a non-cooperation movement and the shutdown of offices, courts and revenue collection. You gave me full support.

Then suddenly, without consulting me or even informing us, he met with one individual for five hours and then made a speech in which he placed all the blame on me, laid all the fault at the door of the Bengali people!

The deadlock was created by Bhutto, yet the Bengalis are the ones facing the bullets! We face their guns, yet its our fault. We are the ones being bitten by their bullets - and it's still our fault!

So, the struggle this time is our struggle for emancipation! This time the struggle is for our freedom!

Brothers, they have now called the Assembly to commence on March 25, with the streets not yet dry of the blood of my brothers. You have called the Assembly, but you must first agree to meet my demands. Martial Law must be withdrawn; the soldiers must return to their barracks; the murderers of my people must be redressed. And power must be handed over to the elected representatives of the people.

Only then will we consider if we can take part in the National Assembly or not.

Before these demands are met, there can be no question of our participating in this session of the Assembly. That is one right not given to me as part of my mandate from the masses.

As I told them earlier, Mujibur Rahman refuses to walk to the Assembly trading upon the fresh stains of his brothers’ blood!

Do you, my brothers, have complete faith in me?

Let me tell you that the Prime Ministership is not what I seek. What I want is justice, the rights of the people of this land. They tempted me with the Prime Ministership but they failed to buy me over. Nor did the succeed in hanging me on the gallows, for you rescued me with your blood from the so-called conspiracy case.

That day, right here at this racecourse, I had pledge to you that I would pay for this blood debt with my own blood. Do you remember? I am ready today to fulfill that promise!

I now declare the closure of all the courts, offices, and educational institutions for an indefinite period of time. No one will report to their offices- that is my instruction to you.

So that the poor are not inconvenienced, rickshaws, trains and other transport will ply normally-except for serving any needs of the armed forces. If the army does not respect this, I shall not be responsible for the consequences.

The Secretariat, Supreme Court, High Court, Judge’s Courts, and government and semi-government offices shall remain shut. Banks may open only for two hours daily, for business transactions. But no money shall be transmitted from East to West Pakistan. The Bengali people must stay calm during these times. Telegraph and telephone communications will be confined within Bangladesh.

The people of this land are facing elimination, so be on guard. If need be, we will bring everything to a total standstill.

Collect your salaries on time. If the salaries are held up, if a single bullet is fired upon us henceforth, if the murder of my people does not cease, I call upon you to turn every home into a fortress against their onslaught. Use whatever you can put your hands on to confront this enemy. Every last road must be blocked.

We will deprive them of food, we will deprive them of water. Even if I am not around to give you the orders, and if my associates are also not to be found, I ask you to continue your movement unabated.

I say to them again, you are my brothers, return now to the barracks where you belong and no one will bear any hostility toward you. Only do not attempt to aim any more bullets at our hearts: It will not do any good!

And the seventy million people of this land will not be cowed down by you or accept suppression any more. The Bengali people have learned how to die for a cause and you will not be able to bring them under your yoke of suppression!

To assist the families of the martyred and the injured, the Awami League has set up committees that will do all they can. Please donate whatever you can. Also, employers must give full pay to the workers who participated in the seven days of hartal or were not able to work because of curfews.

To all government employees, I say that my directives must be followed. I had better not see any of you attending your offices. From today, until this land has been freed, no taxes will be paid to the government any more. As of now, they stop. Leave everything to me. I know how to organize movement.

But be very careful. Keep in mind that the enemy has infiltrated our ranks to engage in the work of provocateurs. Whether Bengali or non-Bengali, Hindu or Muslim, all are our brothers and it is our responsibility to ensure their safety.

I also ask you to stop listening to radio, television and the press if these media do not report news of our movement.

To them, I say: You are our brothers. I beseech your to not turn this country into a living hell. Will you not have to show your faces and confront your conscience some day?

If we can peaceably settle our differences there is still hope that we can co-exist as brothers. Otherwise there is no hope. If you choose the other path, we may never come face one another again.

For now, I have just one thing to ask of you: Give up any thoughts of enslaving this country under military rule again!

I ask my people to immediately set up committees under the leadership of the Awami League to carry on our struggle in every neighborhood, village, union and subdivision of this land.

You must prepare yourselves now with what little you have for the struggle ahead.

Since we have given blood, we will give more of it. But, Insha'Allah, we will free the people of this land!

The struggle this time is for emancipation! The struggle this time is for independence!

Be ready. We cannot afford to lose our momentum. Keep the movement and the struggle alive because if we fall back the will come down hard upon us.

Be disciplined. No nation’s movement can be victorious without discipline.

Joy Bangla! (Victory to Bengal!)

Where do you find one man addressing millions and within ten countable minutes unifying them into one fighting nation? Sheikh Mujibur Rahman did just that on 7 March 1971.

Abu Zubair, author of "The Silent and the Lost" (2011)

In 1948 Muhammad Ali Jinnah said: "If we begin to think of ourselves as Bengalis, Punjabis and Sindhis first, and Muslims and Pakistanis only incidentally, then Pakistan is bound to disintegrate". The blood was still flowing from the murderous communal clashes that followed the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent when Pakistan's founder gave voice to that fear. Last week blood flowed again as the world's fifth most populous nation (130 million), divided between a wheat-growing West with tall, light-skinned people and a rice-growing East with short dark-skinned people, moved ominously toward a breakup.

TIME magazine on 15 March 1971

Further preconditions for negotiation

In this speech Sheikh Mujib mentioned a further four-point preconditions in addition to his Six-Points (6 Dafa) for participating in the National Assembly Meeting on 25 March 1971:

4 additional pre-requisites:

- The immediate lifting of martial law.

- Immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks.

- An inquiry into the loss of life.

- Power handed back to the elected people’s representatives immediately.

Sheikh Mujib avoids unilateral declaration of independence but message loud and clear

Sheikh Mujib urged "his people" to turn every house into a fort of resistance. He closed his speech saying, "Ebarer sangram amader muktir sangram - ebarer sangram amader swadhinatar sangram" (Our struggle is for our freedom. Our struggle is for our independence). The power, passion, and leadership evoked in the speech by Sheikh Mujib, dubbed as "Rajnitir Kobi" (The Poet of Politics), provided the 'green signal' for the declaration of independence.

All of which sent West Pakistan's politicians scrambling to find a solution.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman laid down 10-Point programme in his 7 March 1971 speech for the people to observe:

- No-tax campaign to continue.

- All government offices, including the secretariat, the high court and other courts throughout East Pakistan to observe hartal indefinitely with appropriate exemption to be announced from time to time.

- Railways and ports to function, but railway workers not to cooperate if the railways or the ports were used for mobilisation of military forces for carrying out repression against the people.

- Radio, television and newspapers to give complete version of Awami League's statements, and not to suppress news about the peoples' movement, failing which Bengali workers not to cooperate.

- Only local and inter-district front telecommunications to function.

- All national institutions to remain closed.

- Banks not to effect remittances to West Pakistan either through the State Bank of Pakistan or otherwise.

- Black flags to be hoisted on all buildings every day.

- Hartal to be withdrawn, but complete or partial hartal may be declared at any moment, depending upon the situation.

- A Sangram Parishad (Council of Action) to be organised in each union, mohallah, thana, sub-division and district under the leadership of local Awami League leaders.

The next day [i.e. 2 March 1971], when there was a riot, the Biharis attacked a peaceful procession. This created a huge turmoil. We were in fear that we would be unarmed. I kept my plan secret and took all preparations to foil their move. The historic declaration at Race Course Maidan on 7 March 1971 seemed to me as a green signal. We gave out planning the final shape.

Major Ziaur Rahman, 'Z-Force' and Sector 1 Commander, on the non-cooperation movement from 1st March onward

I had accepted with firm determination Bangabandhu's directive in the speech to continue struggles even if he fails to give orders.

Major Rafiqul Islam, Bir Bikram and Sector 1 (Chittagong) Commander during 1971

We could realize that the West Pakistanis were going to do something dangerous. Therefore, a sentiment had grown among the Bengali soldiers that they would resist, if any blow comes on them. We found a directive in the 7th March speech of Bangabandhu and we started organizing the Bengali soldiers.

Major K. M. Shafiullah, 'K-Force' and Sector Commander

Following Bangabandhu's clear directive for Liberation War, we started taking preparations to resist any attack from the Pakistani army.

Major Abu Osman Chowdhury, Sector 8 Commander, said Sheikh Mujib's speech had helped them to overcome "mental crisis"

It was the best possible address that could be delivered at that time... rightly he did not declared independence which could be counterproductive at that moment, but it contained signal for the Liberation War.

Major Hafizuddin Ahmed, freedom fighter and later a senior leader of BNP

The brief address of Bangabandhu on that day contained a comprehensive guideline for the freedom of Bengalis from the clutches of Pakistan. It was the actual reflection of the hopes and aspirations of Bengali nation in true perspective at that time.

Shahjahan Siraj, freedom fighter and later a BNP minister

The 7 March 1971 speech was very crucial for taking the Bengali officers and soldiers to revolt against Pakistan. For justified reasons, Bangabandhu could not openly call for independence in his speech, but it carried the directive for a total armed struggle...In line with the directives we staged the revolt at 8th Bengal in Chittagong Cantonment under late president Ziaur Rahman.

Colonel Dr. Oli Ahmed, freedom fighter and later the chief of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)

It was a crucial statement at a crucial moment of the nation... He (Bangabandhu) had given the framework of our great independence through this address.

He (Bangabandhu) depicted the picture of disparity towards the then East Pakistan by the Pakistani rulers and called for the war of independence in his address in his own way. As a matured leader he rightly gave the appropriate message in his address at that moment... he gave all the signals in appropriate manner.

Mahbubur Rahman, former army chief and a member of BNP's highest decision making standing committee, who listened via BBC Radio whilst stranded in Pakistan in 1971

[If Sheikh Mujib had proclaimed independence on 7th March] In that case we would have lost the international support or world sympathy... I never agreed with 'ultra revolutionaries' who said he (Bangabandhu) should have declared independence on that day.

It was the best possible address that could be delivered at that time... rightly he did not declare independence which could be counterproductive at that moment, but it contained signal for the liberation war.

Major Hafizuddin Ahmed, liberation war veteran and later Vice-President of BNP, praises Sheikh Mujib for his timing

Mujib virtually became the ruler... His residence (32 Dhanmondi) became the presidency (from March 7)...the command of the central government began to be defied.

Lieutenant General A. A. K. Niazi, Commander of Pakistani troops

Bangladesh had virtually come into being on 7 March 1971.

Mujib started in his usual thunderous tone but gradually scaled down the pitch to conform to the contents of his speech... The crowds that had surged to the Race Course dispersed like a receding tide. They looked like a religious congregation returning from mosque or church after listening to a satisfying sermon. They lacked the fury which might have motivated them to charge on the cantonment, as many of us had apprehended.

These virtually made East Pakistan fully autonomous without formally declaring independence. From this time onwards it was Mujib's writ rather than Yahya's, that ran East Pakistan.

Nitish K. Sengupta, author of "Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib" (2011)

'Dhaka Betar Kendra' airs Sheikh Mujib's speech on 8th March after staff stage walkout

By early March 1971 Pakistani military took control of the Dhaka station of Radio Pakistan. The station was led by Regional Director Ashraf-uz-Zaman, a Bengali.

There was hatred brewing up among the two wings of Pakistan. During the tidal wave and natural calamity of 12 Nov 1970, it was further evident that the Pakistani rulers were indifferent about erstwhile East Pakistan. On 28 February 1971, after returning from an official picnic we saw military guards posted at the gate - "it was for security reasons" they said.

Ashfaqur Rahman Khan, a Program Organiser of Radio Pakistan at Dhaka Station and later a Regional Director of Bangladesh Betar

Major Siddiq Salik, a relatively junior but well known Pakistani officer of the Military Intelligent Agency, used to supervise all the radio programmes on a regular basis. He also instructed which programme would go on air. Nevertheless, in defiance of the military junta's orders the Bengali staff of the station aired news of the non-cooperation movement, demonstrations, slogans and played gono sangeet (folk songs), patriotic songs and dramas.

Ashraf-uz-Zaman ()

Ashraf-uz-Zaman ()  Siddiq Salik ()

Siddiq Salik ()

From 4 March 1971 all the radio stations which were directly under the central government defied all regulations and changed its nomenclature from Radio Pakistan to "Dhaka Betar Kendra". The other stations in Chittagong, Khulna, Rajshahi, Sylhet and Rangpur followed the lead.

At this important juncture the then Regional Director of radio, Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan played a vital role in the history of radio of the country. From this day onwards under the able leadership of Zaman, we brought about a complete change in the schedule and started to broadcast news, documentary, commentary and patriotic songs. News Editor Saiful Bari also played an important role during this time.

Meanwhile, a nucleus team was formed with Assistant Directors Mobzulul Hussain, Ahmed-uz-Zaman and Mofizul Huque, and Program Organisers (myself) Ashfaqur Rahman Khan, Nasar Ahmed Choudhury, Kazi Abdur Rafique, Bahramuddin Siddiqui, Shamsul Alam and Taher Sultan. We were given orders to face any eventuality and we stayed during late hours in shifts at the radio station.

During this time, the agitated students and politicians, journalists and intellectuals had been urging the leaders to take immediate steps to declare independence. The artistes had boycotted the station, but we were able to convince them that the only option for us was to stay united. Soon after, as we know, the artistes formed the "Bikkhubdho Shilpi Somaj". The artistes, journalists, painters took the word to the people, performing on the roads, turning every vantage point into an impromptu stage.

From the evening of 6 March 1971 Radio Pakistan announced that they'd broadcast live Sheikh Mujib's 7th March speech. The repeated announcements made more people aware of the event and subsequently the whole of Race Course Maidan was packed full of people.

We worked under the leadership of the regional director, Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan, who secretly informed us that we are going to broadcast the speech of Bangabandhu defying the ban. We were so excited! On the 6th night, engineers of the radio set up telephone and necessary equipment on the dais at the Race Course.

On 7 March 1971 Ashraf-uz-Zaman, Assistant Director Ahmed-uz-Zaman and Programme Organiser Nasar Ahmed Choudhury took up their positions on the stage from where Sheikh Mujib would address the mammoth crowd. They were supported by Programme Organisers Shamsul Alam and Kazi Abdur Rafique who were below the stage. Posted at the Savar transmitting Center was Program Producer Mir Raihan with the engineering staff. And waiting eagerly at the Dhaka radio station was Program Organisers Ashfaqur Rahman Khan and Bahramuddin Siddique.

Ahmed-uz-Zaman ()

Ahmed-uz-Zaman ()  Nasar Ahmed Choudhury ()

Nasar Ahmed Choudhury ()  Ashfaqur Rahman Khan ()

Ashfaqur Rahman Khan ()  Kazi Abdur Rafique ()

Kazi Abdur Rafique ()  Shamsul Alam ()

Shamsul Alam ()  Mir Raihan ()

Mir Raihan ()  Bahramuddin Siddique ()

Bahramuddin Siddique ()

Sheikh Mujib was supposed to address the crowd at 2.00 pm but he was running a little late. In the meantime, the increasingly bold and daring act of the Bengali radio staff worried the Pakistani administration, so much so that the Chief Martial Law Administrator's headquarters directed the Dhaka radio station to stop the 'nonsense'. Around 2.10 pm, minutes before Sheikh Mujib's historic address, an officer on duty suddenly brought a little note to Ashfaqur on behalf of Major Siddiq Salik. Written in English, Major Salik banned the radio from broadcasting Sheikh Mujib's speech.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's voice or speech shall not be played on radio until further notice from the Administration.

The message was a clear reflection of the anxiety in the garrison over the situation centering the address. It further demonstrated the fear that Sheikh Mujib generated amongst the Pakistani junta with regards to his power of persuasion amongst the masses of the eastern wing.

Ashfaqur took the note quickly to Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan and asked him what to do - to which Ashraf-uz-Zaman simply replied "Leave". Thus, without any further announcements Ashfaqur asked the engineers to switch the machines off and with that all the officers and staffs closed down the transmission and slowly left the heavily guarded premises as a protest against the military regime. They then went to the Race Course Maidan to listen to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. However, there was a powerful radio transmitter in Savar, few miles outside of Dhaka. So the staff at Dhaka station asked the radio workers there to go to hiding so that no programme could be aired on radio.

On 7 March 1971, the historic day, it was still undisclosed that we would broadcast the speech live. An OB team (outside broadcasting) was positioned at the Race Course Maidan, now known as Suhrawardy Uddyan. Throughout the day we played patriotic songs. When the time for the broadcast came, we put the telephone receivers down to avoid phone calls from the military authorities.

Meanwhile, there was a tense situation everywhere. Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan was constantly in liaison with Bangabandhu. He was at the stage and Bangabandhu was due to arrive at the Race Course Maidan to deliver his speech at 2pm. At the station, the seconds seemed like hours as the clock ticked away and we waited impatiently to relay the speech, live.

Despite all our well-laid plans, disaster struck minutes before the speech was on. An official had forgotten to take one telephone of the hook and the call came from the higher authority as we’d feared. Someone brought in a "chit" ordering us not to broadcast anything on Sheikh Mujib until further notice.

However, by 2.35 pm Mujib had reached the venue and began his speech to the nation and we were still in a deadlock on whether we could broadcast the speech or not. I was at the studio end as we tried wholeheartedly to contact Ashraf-uz-Zaman for his final orders from Mujib.

The next few moments were turning points. Ashraf-uz-Zaman went up on the stage to pass on the message to Bangabandhu that we were not allowed to broadcast. He changed his address spontaneously by repeating this to the thousands gathered, urging all from that moment to stop working for the government. Ashraf-uz-Zaman immediately asked us to leave work and come out of the heavily guarded radio station. From there we practically ran to the Race Course. By a stroke of luck, we had an EMI emergency portable recording gear at the stage to record the historic speech.

There were substations at Kalyanpur, Nayarhat and Mirpur, from where the transmission was carried out in case the main station failed. So when we came out of the office we called up the people in charge of the transmission stations and we asked them to evacuate the place. It was for the first time in the history of radio in our country that the transmission came to a total halt.

As the crucial 7 March 1971 - the day Mujib was to address a public rally at Ramna Racecourse - approached, Dhaka became restive with rumors, sears [sudden burning sensation] and apprehensions.

The Bengali friend at the receiving end (radio station) reacted sharply to the order. He said, "if we can't broadcast the voice of the 75 million people we refuse to work". With that the radio station went off the air.

Major Siddique Salik wrote in his book "Witness to Surrender"

At radio's Shahbagh station, it wasn’t an easy ride for the employees. At the very last moment, the military authorities had slapped a ban on the planned broadcast. The employees instantly enforced a strike, compelling the men in uniform to retreat.

BDNews24 website

In the evening the staff gathered at the house of Program Organiser Kazi Abdur Rafique on Elephant Road in Hatirpool area of Dhaka and held a secret meeting to discuss future course of action. Later that evening Ashraf-uz-Zaman received a call from Major General Rao Farman Ali, Advisor to the Governor of East Pakistan (and later a key architect of Operation Searchlight genocide), asking him to restart the broadcasting service immediately. After short and intense exchanges, Ashraf-uz-Zaman negotiated the return of staff on the condition that Sheikh Mujib's speech could be aired.

At 9.00 pm the phone rang. I didn't pick it up. The Awami League member whose house we were in answered. "Sir, Farman Ali wants to speak to you" was the message. I asked how did they knew I was here. He said, "They have many sources. Somehow they found out".

I answered the phone. "Yes, Sir?"

[Farman Ali] "Why is the radio suddenly off?"

"You are responsible for that", I replied.

"We? How are we responsible? Radio must be opened immediately!"

"That's impossible, sir. Radio cannot be opened now. All my employees have gone underground. I have no trace of them".

"Then what is to be done?"

"There is nothing to be done".

"Radio must open by tonight".

"But all my employees are missing, so where can I locate them?".

"So what can you do?"

"I can try under one condition".

"What is that?"

"I must have the permission to broadcast Sheikh Mujib's voice and speech on the radio".

"But how's that possible? The speech is already over".

"That is my affair".

And suddenly, the voice [i.e. Farman Ali] said, "Allowed!"

From the morning it was being broadcast repeatedly, that the speech would be heard directly from the Race Course Field, subsequently the whole field was jam-packed with people. We put the micro-phone into position and with me, I kept a portable EMI tape-recorder. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman arrived a bit late that day, and as he was gearing up to deliver his speech we heard a plane zoom past over-head. It was the plane on which Lieutenant General Tikka Khan was supposed to arrive. The whole mob got fairly excited in the field. Bangabandhu had almost started his speech when suddenly we got a call from the duty-room through the intercom to stop broadcasting immedietely. Major. Siddique Salek threatened Ashfaqur Rahma that if we carried on with the live broadcasting of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speech, they would blow up the Radio Station. Abruptly, the broadcasting was stopped.

Despite the threat, I continued to record the speech secretly on my own. Mr. Ahmaduzzaman (Assistant Director) quickly scribbled on a piece of paper that the Army strictly forbade us to broadcast the speech and handed it to the Radio Director, who then passed it on to the member of the Parliament of Tangail. The speech was already mid-way when it reached Bangabandhu's hand. Those of you who were present there that day, must recall that at one point Bangabandhu said "Just now, I have been informed that they are preventing the media to broadcast my speech". He then requested the staff of the Radio and Television not to report to work unless they allow us to broadcast the speech over the media. The offices and administration were shut down immediately according to his request, but in the meantime the entire mob in the field got panicky hearing the declaration of independence and started to run amock, dispursing which-ever way they could. Yet, I finished recording the whole speech and managed to slip both the tapes inside my shirt. Then I packed up the recorder-stand and descended from the stage to join with Alam, and Kazi Rafique on the ground - I also found the Director [Ashraf-uz-Zaman] standing there and went up to him and whispered "Sir, I have recorded the whole speech on tape". He said "Good Job" and praised me profusely. Then he conveyed the message to the Joint Secretary, Ministry of Information about it who was present there and asked him what should be our next step.

The Joint Secratary ordered us to leave the place and run away, but not to our homes, and added should there be any question, tell them "I said so!". We all went to Kazi Rafique's house in Hatirpul and from there, we instructed the Savar Transmitting Service to shut down the transmission. Within minutes the broadcasting went off the air. I now realized the grave importance of shutting down the Radio Broadcast. It sent a very strong message to the West Pakistanis because the only link they had between them, was the Radio, has been totally severed. They got restless to learn as to what was happening in East Pakistan.

We spent the entire night at Kazi Rafique's house and eventually learned that the Army got hold of the Director of Radio Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan and surrendered to him fully. They even allowed the Director to broadcast whatever he wanted to, in return for the favour, that the Radio Station should not be shut down.

Mr. Ashraf-uz-Zaman Khan came to us and announced that, "Victory is finally ours, the army has surrendered to us fully, but I told them that its not possible to restart the transmission right away, it has to be done tomorrow and on the pre-condition that you must let us broadcast Shiekh Mujib’s speech". They agreed. The preparation for the whole event started to take place, the Engineering Department was notified accordingly to restart the transmission again in the morning, my recorded tapes were played after repeated announcements to the public.

After having convinced Major General Farman Ali to permit them to broadcast Sheikh Mujib's address, Ashraf-uz-Zaman recalled all his staff. They returned to work the next morning at 7.00 am. At 8.30 am Sheikh Mujib's speech was aired on the radio. The contents of the fiery speech thus finally reached every corner of the country, and the non-cooperation campaign began to make greater impact. The speech added the much-needed fuel to the fire, already ignited in the minds of the masses.

The first sounds [in the morning] on the radio was "Radio Dhaka Station", we left out 'Pakistan', "today at 8.30 am we will broadcast Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speech that we recorded yesterday".

That day [i.e. 8 March 1971] was a milestone for more reasons than one. The mood in the stations became defiant and bold. People worked round the clock gathering and relaying news, documentary, speeches anything that would come to the aid of the country. The optimism from that room seemed to become contagious over the airways as it carried news of non-cooperation and hope to people in the remotest corners. From muddied trenches to now empty living rooms, the radio became the day-to-day companion, the one link that tied everyone together.

Few other key contributors who were actively engaged in renaming Radio Pakistan to 'Dhaka Betar Kendro' and broadcasting Sheikh Mujib's historic address include:

- Mofizul Huq - Assistant Director

- Mobzulul Hussain - Assistant Director

- Saiful Bari- News Director

- Jalaluddin Rumi - Program Organiser

- Taher Sultan - Program Organiser

- Shamsul Alam - Program Organiser

- Faiz Ahmed Choudhury - Assistant News Director

Gradually the people of East Pakistan geared up and made all the arrangements for the fight for liberation. From then onwards all the speech of Bangabandhu which was delivered from his residence at Road-32 Dhanmondi and other places were recorded and broadcast without any objection from the Army.

Ashraf-uz-Zaman handed the document containing Sheikh Mujib's speech to his staff member Mirana Zaman for safekeeping. Risking imprisonment if discovered, Mirana and her husband Quazi Akhtar-uz-Zaman, then a manager at Daily Ittefaq newspaper, kept the document in a steel cabinet at the corner of their living room on 39 New Elephant Road. This make-shift vault held the document until the onslaught of war. After that, the couple passed it on to the officials of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, the newly formed independent radio station of Bangladesh. Once the war started Program Organisers Taher Sultan, Ashfaqur Rahman, Ashraful Alam and others fled the Dhaka radio station to join Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra whilst fellow colleagues such as Nasar Ahmed Choudhury stayed back to assist undercover. Jalaluddin Rumi, another Program Organiser, left his job and joined the liberation movement as a Freedom Fighter.

Jalaluddin Rumi ()

Jalaluddin Rumi ()  Mirana Zaman ()

Mirana Zaman ()  Quazi Akhtar-uz-Zaman ()

Quazi Akhtar-uz-Zaman ()

If it took 3 million courageous lives and countless tragedies to win our war, what we should not forget is that it also took a group of dedicated people, who risked it all, to keep the airways and the spirit of the country alive through it all.