Tension increases as political cat-and-mouse game ensues

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

As the year 1971 started, the relationship took a turn for the worse.

The 1970's General Election had a profound impact on Pakistan's political scene. It cemented Awami League's position as the party of East Pakistan and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the voice of Bengalis. The east has long complained that their impoverished region has been exploited by what they call the big business of the wealthier and much more industrialised western wing. Now, through the Awami League victory, they were ready to stand up and take a share of their legitimate right.

The General Election also projected the newly founded Pakistan People's Party, and in particular, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, as the symbol of patriotism. In the political games and formal negotiations that followed, each of the players was committed at the outset to reaching a constitutional consensus and a transfer of power under the rules set forth in the Legal Framework Order (LFO). For Pakistan to revert back to civilian rule and end military dominance, one of these power had to concede defeat.

East Pakistan's elected member's oath of allegiance

Before Yahya could make another move, Sheikh Mujib addressed a huge public meeting at the Ramna Race Course ground, Dhaka, on 3 January 1971. The people gave him the absolute mandate in favour of his Six-Point doctrine, now it was his turn to implement it. Sheikh Mujib conducted a solemn ceremony in which all elected MNAs (members of the National Assembly) from East Pakistan took an oath never to deviate from the 6-Dafa idea when framing the constitution for Pakistan. Though Sheikh Mujib would seek the cooperation of the western wing, he warned the people that they should not be complacent and be prepared for any sacrifice, which might be needed to achieve their rights.

The next day, Sheikh Mujib said that the Six-Point Programme would provide equal quantum of autonomy to the people of the west wing as well. He was also unanimously elected the leader of Awami League in Parliament.

On 8 January 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced at a press conference that an attempt had been made on his life. He warned that conspiracies were being hatched to frustrate the verdict of the people and that he would start a mass movement if the anti-people elements persisted in such activities.

Nitish K. Sengupta, author of "Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib" (2011)

Strong independence stance of Maulana Bhashani, students and others

On 9 January 1971, Maulana Bhashani called a conference of all those "persons [who were] in favour of independence". Newspapers reported that Maulana Bhashani, Mashiur Rahman (General Secretary of the East Pakistan National Awami Party), Ataur Rahman Khan and Commander Moazzam Hussain (a leader of the Lahore Resolution Implementation Committee) had met at Santosh in Tangail district to discuss implementation of a 5-Point Programme which essentially vowed to accept no less than Bangladesh.

The 5-Point programme envisaged:

- The establishment of a sovereign East Pakistan on the basis of the 1940 Lahore Resolution.

- Boycotting of imported goods including those from the western wing.

- A gradual socialisation of the means of production.

- Adherence to the principles of anti-imperialism and anti-Fascism.

- Launching of a mass movement for pressing a referendum on these issues.

Sheikh Mujib started feeling the political pressure mounted on him by the Maulana on the one hand, and the student community, including those loyal to his own party, on the other.

Two years earlier, on 1 December 1968, Siraj Sikder, the leader of the East Bengal Workers Movement, had announced his thesis for the country's independence through an armed guerrilla warfare. Several months later, in April 1969, the coordination committee of the communist revolutionaries of East Bengal had also announced its programme of national independence through armed struggle. And finally in the year of the general election, the Bangladesh Students Union (Menon group), the most influential student body of the time, announced the political programme for establishing an 'Independent People’s Democratic East Bengal' from a public rally at the historic Paltan Maidan on 22 February 1970. People cheered and roared as former leaders of the group, Kazi Zafar Ahmed and Rashed Khan Menon publicly argued for independence through an armed struggle by peasants, workers and people.

Clearly they were going beyond Mujib, who was till then trying desperately to retain the facade of one Pakistan based on two independent units.

Nitish K. Sengupta, author of "Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib" (2011)

The first major talks over Pakistan's political future took place between General Yahya and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman three days after the pro-independence conference in Santosh.

President Yahya meets Sheikh Mujib, "the future Prime Minister of Pakistan"

On 12 January 1971 General Yahya arrived in Dhaka to hold in-depth talks with Sheikh Mujib with the aim of breaking the political impasse. The General wanted to gauge Awami League's commitment to its program and was assured that they were fully aware of its implications.

But contrary to expectation, General Yahya did not fully spell out his own ideas about the constitution. He gave the impression of not finding anything seriously objectionable in Six Points but emphasized the need for coming to an understanding with the PPP in Western Pakistan.

Muktadhara website

The meeting lasted over three hours. Sheikh Mujib categorically told General Yahya that unless the National Assembly was convened immediately the electorate of East Pakistan would develop serious doubts about the willingness of the central government to honour the results of the election. However, this strong stance by Sheikh Mujib was viewed by some Pakistanis in the western quarter as an attempt to eventually break away from Pakistan.

A strong showing at the polls had turned Mujib's head and he was no longer in a mood for compromise. Yahya invited Mujib and Bhutto to the capital, but Mujib turned down the invitation. Yahya swallowed this and instead traveled to Dhaka himself to meet him on 12 January 1971. The postballot Mujib was a different man. He went back on every point of understanding he had reached with the President during their months of talks, on the basis of which Yahya had sought to accommodate him. The intransigence [stubbornness] of Mujib was an invitation to Bhutto to harden his position as well, which was in consonance with the views of the majority in the army junta. Though Mujib had a standing offer to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan, his terms of acceptance had steadily grown unreasonable, to the extent of being unacceptable. It was becoming clear that he was only for secession.

Hassan Abbas, author of "Pakistan's Drift Into Extremism: Allah, The Army, And America's War On Terror" (2005)

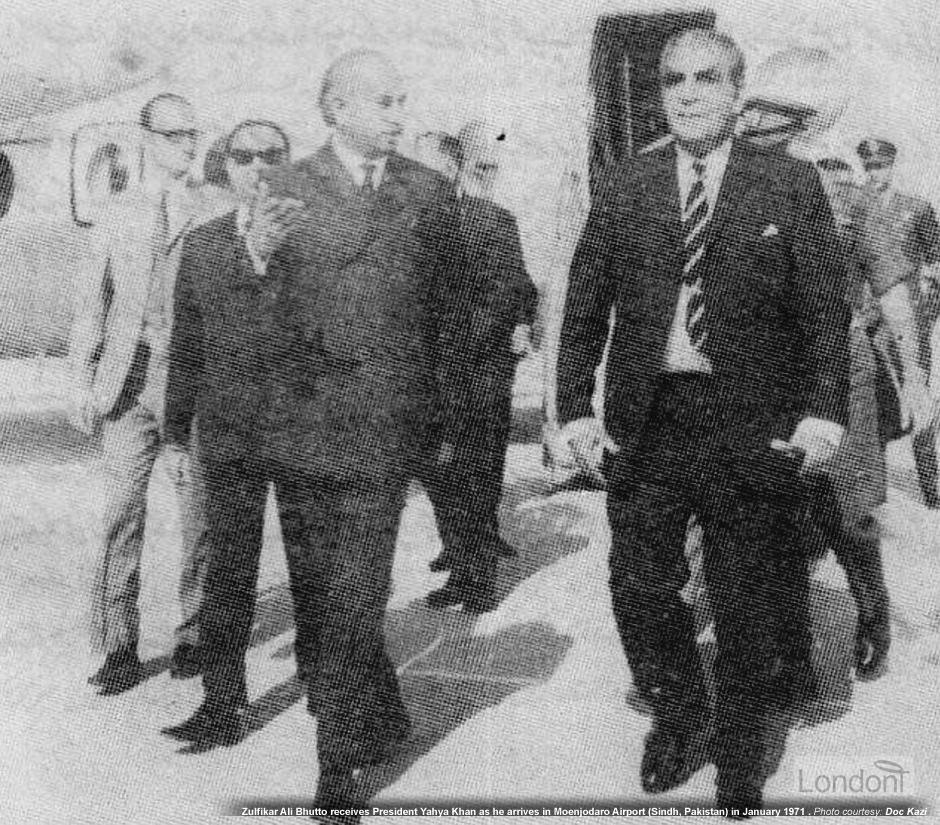

When General Yahya returned to Karachi he described the talks as satisfactory. He referred to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the future prime minister of Pakistan and expressed the hope that the conditions in the country would improve after the new government was installed (i.e. he was not there). Five days later he traveled to Larkana, Sindh, to meet Bhutto.

Relationship between General Yahya, Bhutto and military top brass grows closer

Larkana Conspiracy - mysterious meeting between President Yahya and Bhutto at Bhutto's hometown

On 17 January 1971 President Yahya visited Bhutto at his baronial family estate, Al-Murtaza, in Larkana, Sindh, accompanied by Lt. General S. G. M. Pirzada, Principal Staff Officer to President Yahya, and General Abdul Hamid Khan, Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army and Deputy Chief Martial Law Administrator. Ghulam Mustafa Khar and Mumtaz Bhutto, the PPP leaders from the Punjab and Sind respectively, were also present in the talks.

Till date, a full account of what took place during this trip remains a secret. It is claimed that General Yahya and the other generals went to Bhutto's home on a duck-shooting trip at nearby Drigh Lake. However, the gathering of such high profile personalities aroused suspicion in the Awami League circles, especially since General Hamid had not participated in the Yahya-Mujib talks few days earlier. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman saw this visit as a conspiracy against him and hardened his position.

Yahya's willingness to travel to Bhutto's estate raised further doubts in the minds of the Bengali leadership about the president's impartiality. Not surprisingly, when Bhutto and a delegation from the PPP visited Dhaka on 27 January 1971, Mujib proved to be utterly unmovable on the matter of the Six-Point Programme.

Šumit Ganguly, author of "Conflict unending: India-Pakistan tensions since 1947" (2001)

It is alleged that during the meeting President Yahya told Bhutto that both Pakistan People's Party and Awami League should come to an understanding and, if it became necessary, a meeting between himself, Bhutto and Sheikh Mujib could be held. Bhutto for his part notified President Yahya about the misgivings that the Pakistani army had about Sheikh Mujib and the Awami League. More to the point, he emphasised that the degree of autonomy that Mujib was seeking for the East would amount to virtual secession.

At this [Larkana] meeting, Bhutto called Mujib a "clever bastard" who could not "really be trusted" and wanted to "bulldoze" his constitution through the National Assembly. He also played on the army's beliefs about the fundamental nature of East Pakistan, when he questioned whether Mujib was a "true Pakistani". All this was reflected in Yahya's later comments about Mujib and needing to "sort this bastard out" and "test his loyalty".

Richard Sisson & Leo Rose, authors of "War and Secession: Pakistan, India and the Creation of Bangladesh" (1990)

Various options for the situation was also discussed, such as the formation of a coalition government with smaller parties. Some have even suggested that the potential 'military solution' if Sheikh Mujib did not change his attitude was also framed here.

Bhutto entertained his guests lavishly. There at Bhutto’s lush palace, through the 'Larkana Conspiracy', the blueprint of Operation Search Light was taking shape. While the homework was being done by Bhutto and the top generals, the president mostly remained busy with what he liked the most—the two 'W's [i.e. women & whisky]. Then on, the president was said to be reduced to a signatory or front man only, the real authority rested on the military junta headed by General Hamid and General S. G. M. Peerzada, chief of the general staff to the president and a close friend of Bhutto.

Bhutto, the runner-up in this contest, was an Oxford-educated lawyer from an aristocratic family. He was at the forefront of pro-democracy protests in West Pakistan against President Yahya. He would not let his dreams of becoming the Prime Minister slip away quite so easily.

That Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was no great respecter of democracy is evident from his attitude towards the Awami League, which had secured majority in the 1970 elections.

Ravi Shekhar Narain Singh, author of "The Military Factor in Pakistan" (2008)

Bhutto: "I have the key of the Punjab Assembly in one pocket and that of Sindh in the other"

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto believed that his victory in Sindh and in particular in the powerful Punjab - the two most populous provinces in West Pakistan - made him the chief spokesman of West Pakistan, and without the support of these provinces no credible government could be formed in Pakistan. He was not going to be denied his 'right' to play a, if not the, central role in the changes that lay ahead - not by the Awami League, and not by the military.

Punjab and Sindh are bastions of power in Pakistan. Majority alone does not count in national politics. No government at the centre could be run without the co-operation of the PPP...I have the key of the Punjab Assembly in one pocket and that of Sindh in the other...The rightist presss is saying I should sit in the opposition benches. I am not Clement Attlee [a former Prime Minister of UK and longest-ever serving Leader of the Labour Party].

This veiled threat further jeopardised the chances of reconciliation between the two key parties post the general election.

The other parties of West Pakistan were more willing to work with Awami League. Jamaat-i-Islami had already called on General Yahya to hand over power to the Awami League and the Muslim League and National Awami Party (NAP), which questioned Bhutto's right to speak for all of West Pakistan, would in time show willingness to work with the Awami League.

PPP won most of its seats in rural Sindh - but not in the provincial capital Karachi where Muhajirs denied Bhutto victory - and in Punjab, only two of Pakistan's four provinces. Thus, Bhutto could not lay claim to represent all of West Pakistan, at least not in the manner that the Awami League could in East Pakistan.

Possible reasons why West Pakistani power elite were not enthusiastic about handing over power to the Awami League and East Pakistan:

- Pakistani power elite viewed the Six-Point Programme as secessionist. Sheikh Mujib was viewed as challenging the institutional frameworks of the state in order to address ethnic grievances, whereas Bhutto was viewed as working within the frameworks, similar to Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy.

- The military was wary of the Awami League's ultimate objectives, and the strategic and military implications of the Six-Point plan. Bengali nationalism had become both more strident and vociferous soon after the Indo-Pak war of 1965, leading the military to suspect 'the Indian hand'.

- The military was also concerned with the Six-Point plan's impact on its budget. The Awami League was not likely to support spending upwards of 60% of public expenditures on an institution which included no more than a token number of Bengalis, and, for all intents and purposes, was not defending East Pakistan.

- The powerful West Pakistani commercial concerns that controlled industrial production and jute exports in East Pakistan feared loss of their property and influence if the Six-Point plan were to be implemented. West Pakistan's industrial producers, who sold half of their products in the captive East Pakistan market, were also unlikely to support either reshaping or resizing. To the contrary, they were likely to push for maintaining the status quo.

- Bhutto's success in Punjab province showed the military that he was more than a Sindhi nationalist and had incentives to work through the political centre.

- Bhutto's based in Punjab, from where the military recruited most of its soldiers, made the PPP and the military tacit allies. Bhutto avoided criticising the military in public pronouncements, and went out of his way to point out to the generals that they needed him and the PPP to protect Pakistan.

- Class interests too, tied Bhutto to the centre. Sindhi landlords had always relied on central authority - British as well as Pakistani - to keep feudalism in place. By contrast, Awami League was largely middle class and peasant based, and Sheikh Mujib was not a member of the oligarchy. Class interests did not tie the spokesmen of Bengali nationalism to the oligarchy in West Pakistan, nor was there a need for state power to enforce feudal rights.

- Military believed Bhutto could govern (West) Pakistan, but Sheikh Mujib could not. Bhutto posed as champion of West Pakistani rights and shown he could rise above Sindhi nationalism, especially after a strong performance in Punjab in the general election. In contrast, Sheikh Mujib would have lost his hold over East Pakistani nationalists had he chosen such a course of action.

- Bhutto argued Awami League had no representation in West Pakistan it was not a national party and required PPP, or another West Pakistani party, to rule 'effectively' and 'speak for Pakistan as a whole'.

- The smaller parties of West Pakistan were too divided and weak to serve as the basis for a viable government.

- Bhutto's province of Sindh provides West Pakistan with its only access to the sea, and as such is of critical economic and strategic value to Punjab. East Pakistan had no such direct value for West Pakistan. Thus, Bhutto had greater bargaining position than Sheikh Mujib.

- Karachi, Sindh's provincial capital, had been the premier commercial and industrial centre of Pakistan. East Pakistan's urban and commercial centres did not have the same status.

Bhutto manipulated these apprehensions to alter the balance of power to his own advantage, conducting a war of manoeuvre over borders that would help him win an incumbent struggle within the existing Pakistan regime. He successfully depicted his own position to be in concert with the interests of the West Pakistani establishment. He emphasised that the Awami League's demand for reshaping Pakistan was tantamount to resizing it, which allowed him to assume the patriotic high ground. In essence, he adroitly tied his own political fortunes to perceptions of the Awami League's secessionist aims. In this, Bhutto followed in the footsteps of Randolph Churchill, the Marquess of Salisbury, and Joseph Chamberlain in Britain in the 1880s, and Charles de Gaulle in France before 1958, all of whom used the spectre of contraction to advance their political careers just as they opposed it publicly.

...Bhutto may have guessed that, face with a zero-sum choice, the military would choose Sindh, but he left nothing to chance. He downplayed Sindhi nationalism at the height of the crisis, and focused the limelight on East Pakistan. He was so successful in this, that, for instance, West Pakistani commercial interests looked to Bhutto to protect their property from the Six-Point plan, although Bhutto planned to deal with their interests in Sindh and Punjab in like manner. Bhutto crafted his position to reflect the views and goals of those who rejected negotiations with East Pakistan, and accepted Mujib as Prime Minister as a prelude to meaningful talks. His posturing as defender of West Pakistan was overt, while his role as champion of Sindh was implicit. The military, therefore saw in Bhutto the opportunity to institutionalise a workable arrangement with Sindh, which could be left to Bhutto to control, and to suppress East Pakistan, all in the same breath.

...At the height of the crisis, Bhutto would secretly offer Mujib that if he became the Prime Minister of East Pakistan, and Bhutto that of West Pakistan, that they would leave each other alone, a de facto contraction of the state from its eastern wing. Championing Pakistani nationalism while in practice manipulating the cleavages that prevented it from integrating all Pakistanis, would thenceforth become a hallmark of West Pakistani politics, and a primary cause of the state's continual struggle to consolidate.

Brendan O'Leary, Ian S. Lustick & Thomas Callaghy, editors of "Right-sizing the State: The Politics of Moving Borders" (2001)

This sense of concealed distrust cast a dark shadow over the impending talks between Sheikh Mujib and Bhutto.