"Indifferent" government response

The day after the storm struck the coast, three Pakistani gunboats and a hospital ship carrying medical personnel and supplies left Chotrogram for the islands of Hatia, Sandwip and Kutubdia. Teams from the Pakistani army reached many of the stricken areas in the two days following the landfall of the cyclone.

President Yahya arrives two days later and takes a week to declare cyclone a "major" crisis

Two days after the cyclone hit, President Yahya Khan arrived in Dhaka after a state visit to Beijing, China and overflew the disaster area. The president ordered "no effort to be spared" to relieve the victims. But the people of East Pakistan saw with dismay and anger that the relief operations conducted by the Central Government showed much apathy towards the gigantic needs of the victims. It took one prolonged week for President Yahya Khan to assess the severity of the flood situation and declare the affected area as a "major calamity area". He ordered that all flags should be flown at half-mast and announced a day of national mourning on 21 November 1970.

I can't help people criticising. The point is, my government and my people are at it [i.e. support work] the whole time. My job is get on with the work and forget the criticism.

I am satisfied and I am going to satisfy myself more [that enough relief work is being carried out]. If I'm not satisifed on this tour, I shall do something about it.

President Yahya says he's satisfied regarding the relief efforts

President Yahya left a day after his arrival. His Western Pakistani-dominated central government's seeming indifference to the plight of Bengali victims caused a great deal of animosity. The suffering of the cyclone victims, once again, showed that East Pakistanis were being treated as second-class citizens of Pakistan. The feeling now pervaded in every village and every slum that they must rule themselves. Political leaders in East Pakistan were deeply critical of the central government's initial response to the disaster.

Pakistan's military dictator, General Yahya Khan stopped in Dhaka on his way back from China to West Pakistan. His first point of order was to attend a party at the residence of a Bengali businesswoman that evening.

After the party was over, he flew directly back to West Pakistan. The President of Pakistan, General Yahya Khan, did not feel it necessary to visit the people of his country who had fallen victim to the cyclone. Apparently, even the Governor of East Pakistan was too preoccupied to tend to the matter.

Bengalis were shocked and enraged by this step-motherly treatment meted out by the provincial and central governments of Pakistan. If the people didn't already feel it before, this was surely a wake up call. The autonomy of East Pakistan was essential for the survival of the Bengali people.

In a move reminiscent of George W. Bush's fly-over of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina [2005], Pakistani President Yahya Khan reportedly passed over the delta in Fokker Friendship aircraft, declared that the damage to the region had been exaggerated, and then assigned a subordinate to direct relief efforts rather than tackling the issue himself. Only after the world press began publishing pictures of bodies dangling in tree tops and hollow-eyed, traumatized children did the West Pakistani government stir to action.

People of East Pakistan realised and resolved that from now on they should be able to deal with natural calamities on their own resources.

Very little resources assigned to relief work

East Pakistani rescuers led by relief commissioner Abu Mohammad Anisuzzaman, with the aid of relief supplies pouring in from all over the world, were racing desperately against time and the threat of wide-scale epidemics to save thousands of men, women and children. Communications had been destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of square miles were cut off from all aid except by helicopters. And though relief supplies were steadily piling up in Dhaka thanks largely to the tons of supplies from many nations abroad, the helicopters required to transport them to the remote locations were pitifully few - only one had been made available for relief work in East Pakistan by 18 November 1970. Some helicopters have been offered by the United States of America, but there were very little time to organise large-scale relief operations especially as many of the disaster zone were isolated.

Most of the storm-hit areas were inaccessible and larger transports were too fast for the pinpoint dropping necessary. Another problem had been getting the material from the city's warehouses to the disaster-stricken areas. Small boats and helicopters were best suited for the job and they were brought into use few days after the tragedy occurred. These helped to distribute food, material and medicine as well as personnel, which until then were stranded at Dhaka Airport.

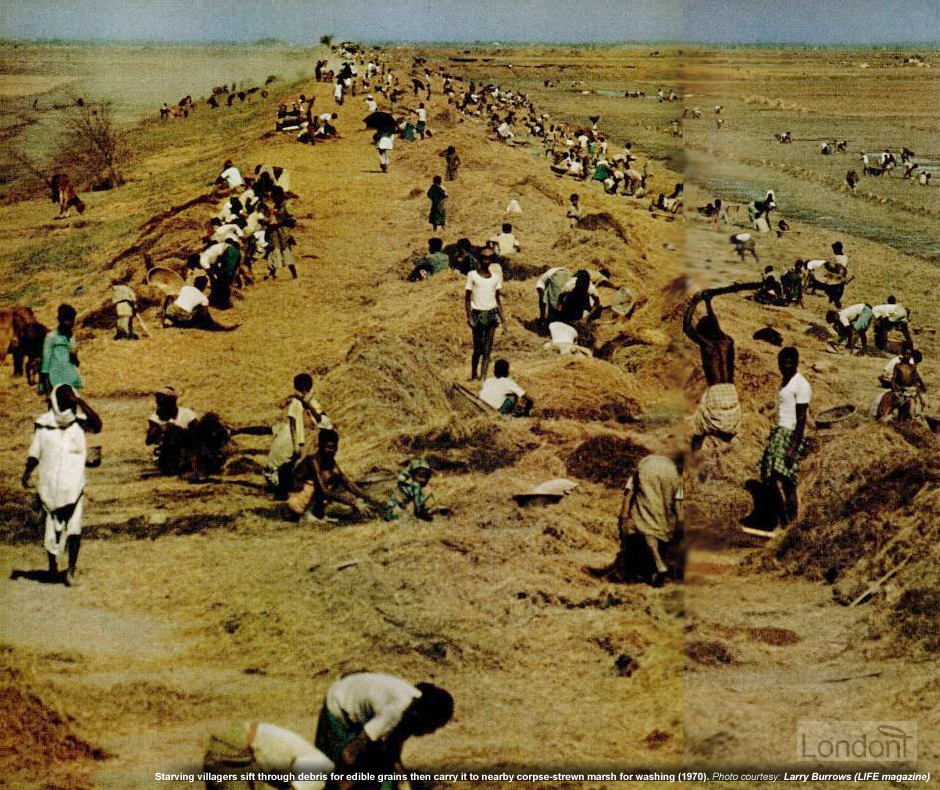

On 19 November 1970, a week after the cyclone struck, a Pakistan Army helicopter flew over the Bhola and Kutubdia islands in the Bay of Bengal dropping the first rice supplies to reach starving villagers who survived the cyclone and tidal wave. At one place the helicopter landed, the local leaders had to beat back their people to allow the rice to be fairly distributed. As the helicopter flew over the devastated villages, people would run towards it through the ruined paddy-fields. The helicopter would drop sacks of rice to the starved villagers - their first food since the disaster took place eight days ago.

When the helicopter landed at one point, the crowd of starving islanders was so large and desperate for food, that their own village leaders had to beat them back with sticks to ensure fair distribution of the rice. When the rice was being handed out the crowd again become disorderly and threatened to overwhelm the men distributing it. Again they were beaten back by their leaders and the food grain given out. However much they get at this stage it is not enough.

The helicopter was carrying only five tons of grain and made two runs over the area. In the next few days, helicopters from the United States and Britain together with British shallow-draught boats arrived to aid operation in the area.

It has taken more than a week since the cyclone and tidal wave struck for the relief operation to get into full swing. Over the past few days fears have mounted of starvation among survivors. Tons of supplies have been mounting at Dacca airport, awaiting transportation to the disaster area. With the arrival of the British task force from Singapore and a build-up of relief equipment and manpower from other countries, the mountain of supplies will be removed to the devastated islands in the Bay of Bengal. Petrol supplies have been flown from Dhaka to the British base at Patuakhali, about 150 miles (240 km) southwest of Dhaka on the perimeter of the devastated area. They'll be used to fuel smaller helicopters carrying out large sweeps of the islands to determine where the supplies are most urgently needed. American helicopters are carrying out similar operations from their base at Noakhali.

In the ten days following the cyclone, one military transport aircraft and three crop-dusting aircraft were assigned to relief work by the Pakistani government. The Pakistani government said it was unable to transfer military helicopters from West Pakistan as the Indian government did not grant clearance to cross the intervening Indian territory, a charge the Indian government denied.

By 24 November 1970, the Pakistani government had allocated a further £80 million to finance relief operations in the disaster area. Yahya Khan arrived in Dhaka to take charge of the relief operations on 24 November 1970. The governor of East Pakistan, Vice Admiral S. M. Ahsan, denied charges that the armed forces had not acted quickly enough and said supplies were reaching all parts of the disaster area except for some small pockets. The Bhola Cyclone further alienated East Pakistanis from the West Pakistan-based central administration because the former felt that the government had been unsympathetic and sluggish in administering relief.

The new experience had only brought into sharp focus the basic truth that every Bengali has felt in his bones, that we have been treated so long as a colony and a market.

4 December 1970: President Yahya said people dying "was not his fault" on the eve of General Election, which would be won by East Pakistanis

On 4 December 1970, President Yahya made a formal mention to the distress of the flood victims of East Pakistan in an address to the nation.

President Yahya said there was a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the disaster. He also said that the general election slated for 7 December 1970 would take place on time, although eight or nine of the worst affected districts might experience delays, denying rumours that the election would be postponed.

The resources that my country has, within the capacity and capability that my people have, everything possible that has been done is being done and will be done. It’s not ideal – but I'd like to know a country which can achieve an ideal.

As I told you a disaster of this kind takes time to mount an operation, well planned operation, not haphazard running around like madman will nothing will happen.

...When the cyclones did come, people died. Not my fault. My fault would begin to take shape when I do nothing for the survivors. And to that extent, towards that end, I explain to you, that I and my government have done the damnedest to see that the survivors survive.

"Everything possible has been done" - President Yahya on cyclone relief work

Three days later the people of East Pakistan voted in the General Election. The result would cause shockwave in West Pakistan. President Yahya and his government would have to prepare for the worst case scenario: the breakup of Pakistan.

With the disregard shown by the Yahya government towards the victims of the cyclone, not only did East Pakistani politicians demand the leader's resignation, but people openly called for what had hitherto been left unsaid: the breakup of East and West Pakistan. It was now only a matter of when.