Build up to the Great Bhola Cyclone

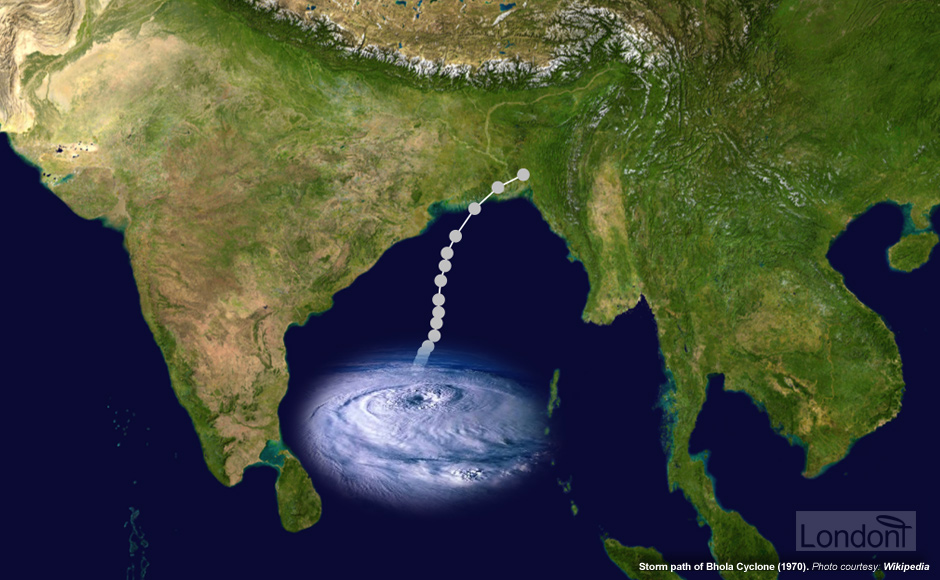

On the morning of 8 November 1970 a major cyclone formed over the central Bay of Bengal. This new and deadly cyclone possibly resulted from the tropical storm that arose in the South China Sea and then moved west over the Malay Peninsula on 5 November 1970 into the Bay of Bengal. This unnamed cyclone intensified from 8 November to 11 November 1970 and head northward towards East Pakistan.

Lack of preparation after early detection

The Indian government received many ship reports from the Bay of Bengal that were giving meteorological information on the cyclone, but as Indo-Pakistani relations were generally hostile, the information was not passed on to the Pakistani government. India's Meteorological Department upgraded it to a cyclone storm on 9 November 1970, and to a severe cyclonic storm two days later.

On 11 November 1970 the U.S. officials notified the Indian and West Pakistani authorities after its weather satellites spotted a storm of at least category 1 intensity tracking up the Bay of Bengal. However, neither nation initially did much to prepare for the coming disaster.

The following day, on 12 November 1970, the Pakistan Meteorological Department did issue a report calling for "danger preparedness" in the coastal regions. As the storm neared the coast, a "great danger signal" was broadcast on Pakistan Radio. Survivors later said that this meant little to them, but that they had recognised a No. 1 warning signal as representing the greatest possible threat. And since radio ownership was most common in and near urban centres, while the inhabitants of the coastal provinces and char islands, who were in much greater danger from the storm, had least access to electricity or radios, meant these warnings were heard by those least in need of hearing them. However, it is estimated that 90% of the population in the area was aware of the cyclone before it hit since they had received minor storms a week leading to the tragedy - but, underestimating the ferocity of the cyclone, only about 1% sought refuge in fortified structures.

Even if the Pakistani authorities had gotten out word about the storm's impending landfall it is unlikely that much could have been done to save lives. In most of the threatened area, there was simply no high ground to which to flee, and the lack of roads or motorized water transport made large-scale evacuation into the interior impractical. As a result, most families in the Ganges delta had little warning of the upcoming storm until howling winds began to batter their rudimentary houses shortly before midnight.

Sudden attack at midnight shocks local

The cyclone made landfall near Chittagong during the evening of 12 November 1970 about the same time as the day's hide tide. The Chittagong meteorological station, located 59 miles (95km) to the east, recorded sustained winds of 89 mph before its anemometer (device to measure wind speed) was blown off. A ship in the port reported a gust of 138 mph (222 km/h) wind. The storm pushed a 33-foot-high (10m) surge across the Ganges delta into Chittagong - that's roughly the equivalent of a two storey building.

Stealing into the Bay of Bengal from the southwest, it whipped the waves into a fury. The narrow neck of the bay is so shallow that water couldn't flow back to sea in a deep undercurrent - as happens when waves build up off other coasts. Instead, water surged over the low land, wiping out whole villages.

Nicknamed the (Great) Bhola Cyclone, the storm struck during a full moon night causing astronomically high tides - by adding another 10ft (3m) to mean sea level - due to the moon's gravitational pull. It hit the south coast with winds of 150 mph (225 kph) and a 20-foot (6m) high storm surge therefore it was high enough to completely flood even the raised houses in the Ganges delta's char islands. Thousands of people were washed away, while they were still asleep.

The people endured the cyclone only by chance, each one of them alone in the night, solitary amid all those panicked, screaming millions of others. Their land, the lush and thickly populated Ganges Delta of East Pakistan, sustained a catastrophe historic in its savage proportions.

It was pitch dark but suddenly I saw a gigantic, luminous crest heading toward our village.

Abdul Jabbar managed to survive but most of his neighbors were less fortunate,

The timing of the Bhola cyclone was unfortunate in other ways as well. The storm struck shortly after the first week of November, a time when tropical cyclones were normally quite infrequent, so many delta farmers no doubt dropped their guard. This problem was compounded by the fact that the storm made landfall in the early morning hours when people were asleep in their beds.

Furthermore, the cyclone impacted the region right before the start of the November rice harvest season. This was doubly unfortunate since not only were flood stocks in the region fairly low at this point in the agricultural cycle, but also the harvest itself had attracted as many as a half-million migrant workers from farther north in Bangladesh hoping to make some cash as day labourers. These migrant farmers, who often slept in the open alongside the fields they harvested, were particularly vulnerable to the cyclone's storm surge.

Most affected areas are highly populated islands and coastal areas

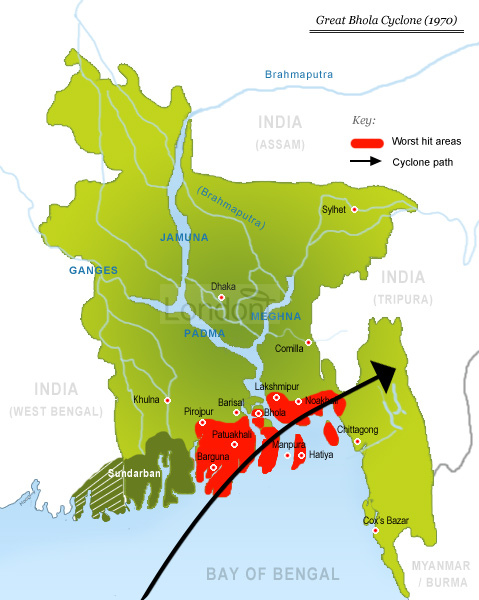

The Bhola cyclone struck the small islands of the Ganges delta - known locally as char. These extremely flat piece of land are the 'by-product' of sediments disposed by the great number of rivers flowing through Bangladesh. They are densely populated and home to over 600,000 inhabitants.

During the Great Bhola Cyclone the southern coastal areas of Perojpur, Barguna, Patuakhali, Bhola, Lakhsmipur and Noakhali districts were the hardest hit. The greatest devastation hit the islands of Hatiya and Dakhin Shahbazpur, part of which was washed into the sea. The hurricane winds also battered Chittagong, Khepupara, north of Char Burhanuddin, Char Tazumuddin, south of Maijdi, and Haringhata. In Manpura Island, 25,000 of its 30,000 people died in the surging waters. Most of the island's cattle, sheep, goats and buffaloes were drowned.

The storm affected a total area of nearly 4,000 square miles, covering a number of off-shore islands in the Bay of Bengal, with an estimated population of 4.8 million. The most severely ravaged area, the delta islands and low-lying coastal plains, measured about 1,700 square miles and contained about 2 million people.

The cyclone ravaged the area leaving behind destroyed houses, roads and bridges, huge holes in the streets and enormous erosion along the streams.

The receding waters spelt only new horror. Those on the islands far offshore were simply given up.

Worst-hit areas were the islands of Hatiya, a heavily populated rural area, and Bhola and the Noakhali area, 120 miles south of Dhaka. Cameramen who landed in these areas by helicopter were begged for food by starving survivors, while survivors still strong enough buried their dead - wearing masks to protect them from the stench of dead bodies.

The people in this area are poor. Densely packed together on land just a few feet above sea level, they eke out [achieve with great effort and strain] a meager existence as fishermen, boatmen, or small-scale farmers.

They are as good as dead. We have to concentrate on the ones we can help.